Three reasons why MTC isn’t working as the Bay Area’s network manager

Image source: MTC

Seamless Bay Area believes that to create a rider-focused, integrated, world-class transit network that brings together 27 fragmented systems, a clear lead “network manager” authority is needed with the mandate, resources, and institutional structure to improve mobility for all.

Recent research affirms that the existence of a network manager entity is a near-universal feature of regions with high transit use across the world, from Milan to Vancouver to Sydney. While many institutional arrangements exist, successful network managers oversee a common set of transit system responsibilities on behalf of all jurisdictions or agencies within a region, including overall network design, fare policy and collection, and route and schedule coordination.

But while this strikes many people as sensible, we are often asked, “Doesn’t the Bay Area have a network manager already? Why can’t the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), which seems like it is supposed to coordinate transportation across the nine-county Bay Area, just do those things?”

So we’re dedicating this blog post to clarifying what MTC’s powers are, and why it has never become an effective Bay Area network manager in its fifty years of existence. Based on our research, the key problem isn’t MTC’s lack of a clear mandate, but rather three other related problems:

The mandates of dozens of other transit agencies and planning entities conflict with MTC’s mandate to coordinate.

MTC’s board composition results in policy shaped too heavily by local interests and not enough by shared regional interests.

MTC policies are shaped too heavily by boards and committees that don’t have enough relevant technical expertise, and are insufficiently informed by best practices and professional experts.

Upon exploring each of these problems further in this blog post, in a future blog post we’ll evaluate different options for creating a Bay Area network manager, including options to house it at MTC, or within another regional body.

Features of effective network managers

According to recent research funded by the Mineta Transportation Institute on regions with excellent transit systems -- where 10-30% of all trips are taken on transit, compared to just 5% of all trips in the Bay Area -- network managers typically oversee the following common functions:

Planning & network design

Fare policy & collection

Schedule coordination

Marketing/public information services

Procurement and contracting of services

Monitoring and enforcement of service standards

A further important observation in the Mineta-funded research is that effective network managers in other regions have clear relationships with the local jurisdictions and transit operators they are intended to coordinate.

What is MTC and what powers does it already have?

When it was created by an act of the California State Legislature in 1970, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission was intended by many to be a network manager - specifically to “integrate feeder bus and rail systems with the fledgling BART system,” according to MTC’s website. However, MTC is neither a state agency (such as the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, BCDC) nor a local jurisdiction (such as a county) so its legitimacy to carry out its mandate is largely dependent on the constituent nine counties that make up its governing structure.

Despite the intent with which it was created, our current transit system’s state of fragmentation is proof of MTC’s limited effectiveness at carrying out the role of network manager. Over the past fifty years, riders have endured a lack of coordinated routes, fares, schedules, and branding - and these things have regularly been identified as barriers to an efficient and effective transit system. In an attempt to “fix” MTC, its mandate has been altered numerous times by state legislation and adopted resolutions at the commission. The timeline below, recently presented to the Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force by MTC staff, shows just how many times legislators have tried to get MTC to step into the role of a network manager. Yet, over the same fifty years, the number of transit agencies -- and associated fares structures, maps, etc -- has multiplied, per capita transit ridership has remained flat, and driving has increased.

Timeline of past legislation to get MTC to be a network manager for Bay Area transit though changes to MTC’s mandate alone. (Source: MTC, Dec. 14, 2020 Blue Ribbon Task Force Meeting Packet)

A review of the current Government Code reveals that MTC (“the commission”) has a relatively clear mandate to coordinate transit, at times with a surprising degree of specificity:

For example, on fares and schedules:

66516. The commission, in coordination with the regional transit coordinating council... shall adopt rules and regulations to promote the coordination of fares and schedules for all public transit systems within its jurisdiction. The commission shall require every system to enter into a joint fare revenue sharing agreement with connecting systems consistent with the commission’s rules and regulations.

On consolidating functions or entire agencies:

66516.5. The commission may do the following: (a) In consultation with the regional transit coordinating council, identify those functions performed by individual public transit systems that could be consolidated to improve the efficiency of regional transit service, and recommend that those functions be consolidated and performed through inter-operator agreements or as services contracted to a single entity.

On the topic of regional rapid transit compatibility:

66515.5. Any public multicounty transit system entirely within the region using an exclusive right-of-way shall incorporate physical characteristics compatible with the system of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART), and provision shall be made for the unified management and operation of any interconnecting facilities.

On the conditioning of funds to transit agencies to require compliance with regional standards:

99314.7. (a) In allocating funds for operating purposes...the Metropolitan Transportation Commission shall apply the following eligibility standards to the operators within the region:… (2)...an operator shall not receive any funds pursuant to Section 99313 or 99314 [i.e. State Transit Assistance Program, or STA funds] unless it has complied with the applicable rules, regulations, and recommendations adopted by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission pursuant to Sections 66516 [i.e. fare, schedule coordination] and 66516.5 [i.e. recommending service consolidation or and mergers].

So to summarize - MTC not only has the ability to set common regional fares and schedules, recommend functional consolidations, and require interoperability of systems, but it has been specifically directed to withhold funding to enforce these policies since at least 1997.

So why doesn’t MTC do these things? Based on Seamless Bay Area’s review of literature, statutes, and interviews with dozens of leaders over the past several years, the primary barrier is not MTC’s lack of adequate legislative mandate - but other conditions relating to the governance of MTC and the region’s dozens of other transportation institutions that make it almost impossible for MTC to carry out this mandate.

Problem 1: The mandates of dozens of other transit agencies and planning entities conflict with MTC’s mandate to coordinate.

Each of the Bay Area’s 27 transit agencies has its own explicit legal mandate to determine its own fares and service, setting up a conflict with MTC’s mandate to coordinate fares and service.

For example, the government code sections for BART, AC Transit, and VTA include nearly identical language giving their boards authority to set fares, with no reference to each board’s need to coordinate with MTC or other actors:

The rates and charges for service furnished pursuant to this part shall be fixed by the board and shall be reasonable.

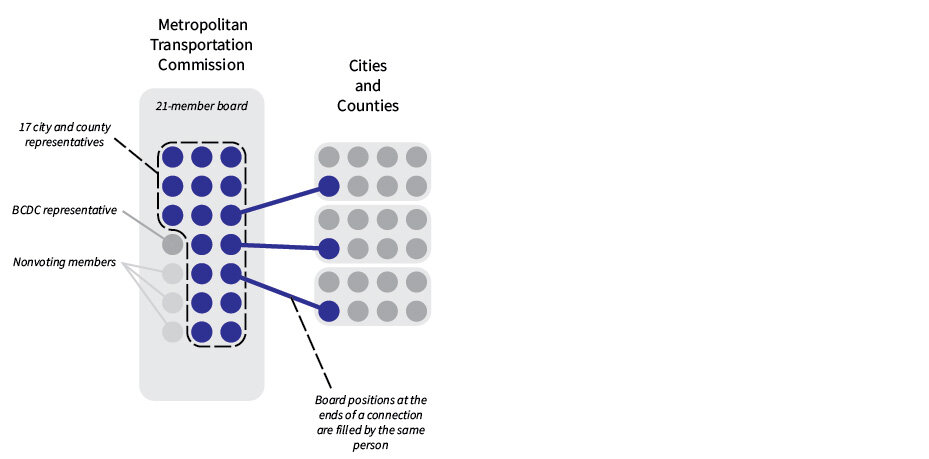

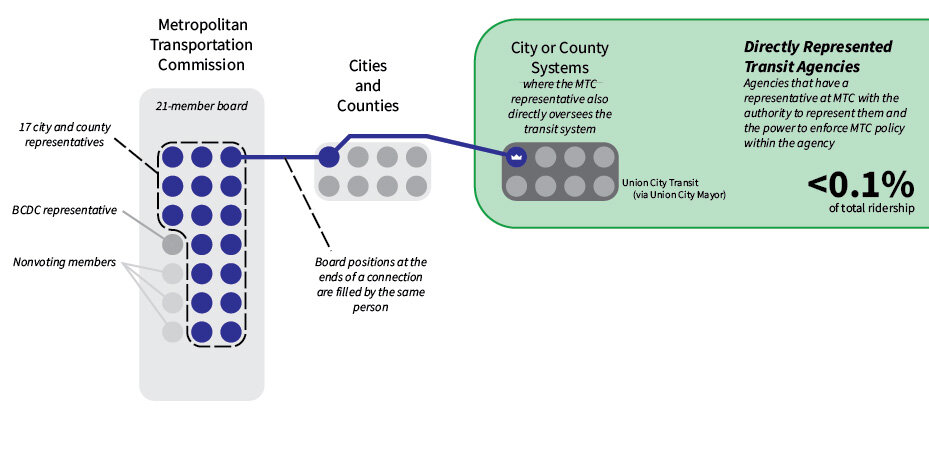

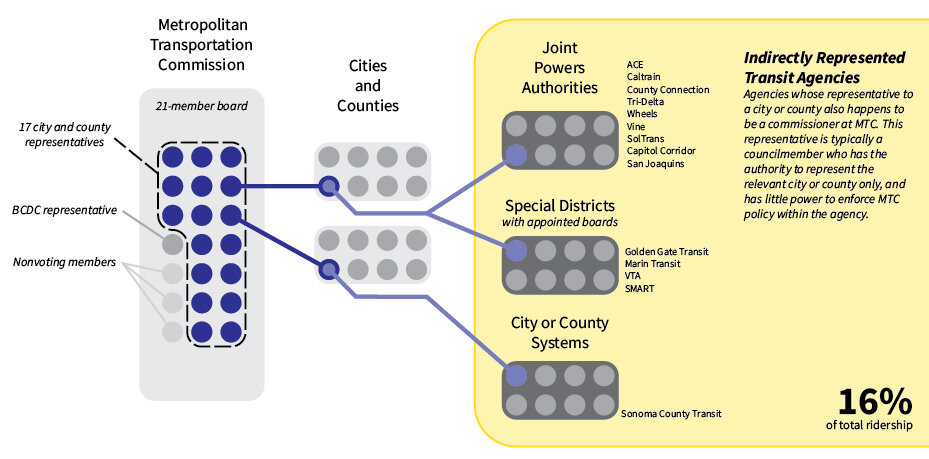

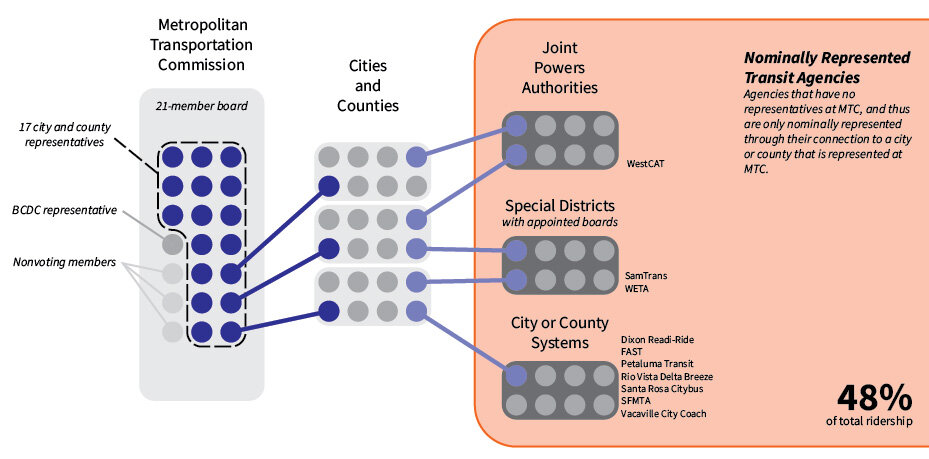

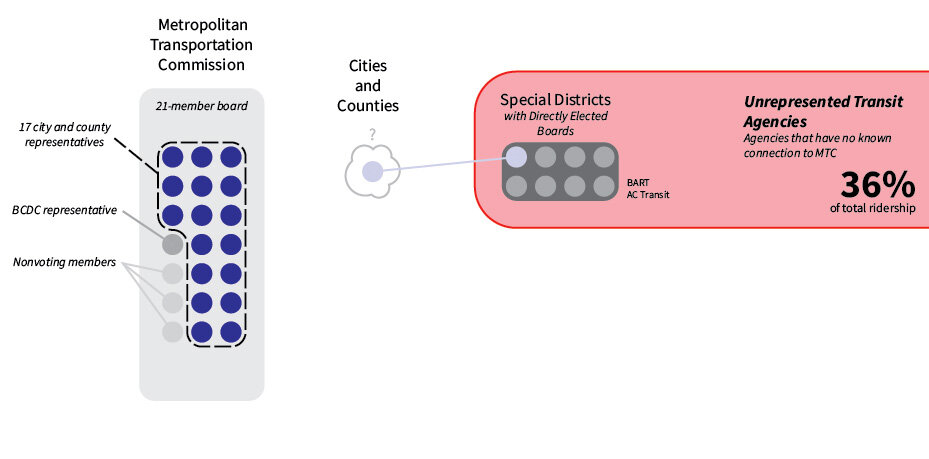

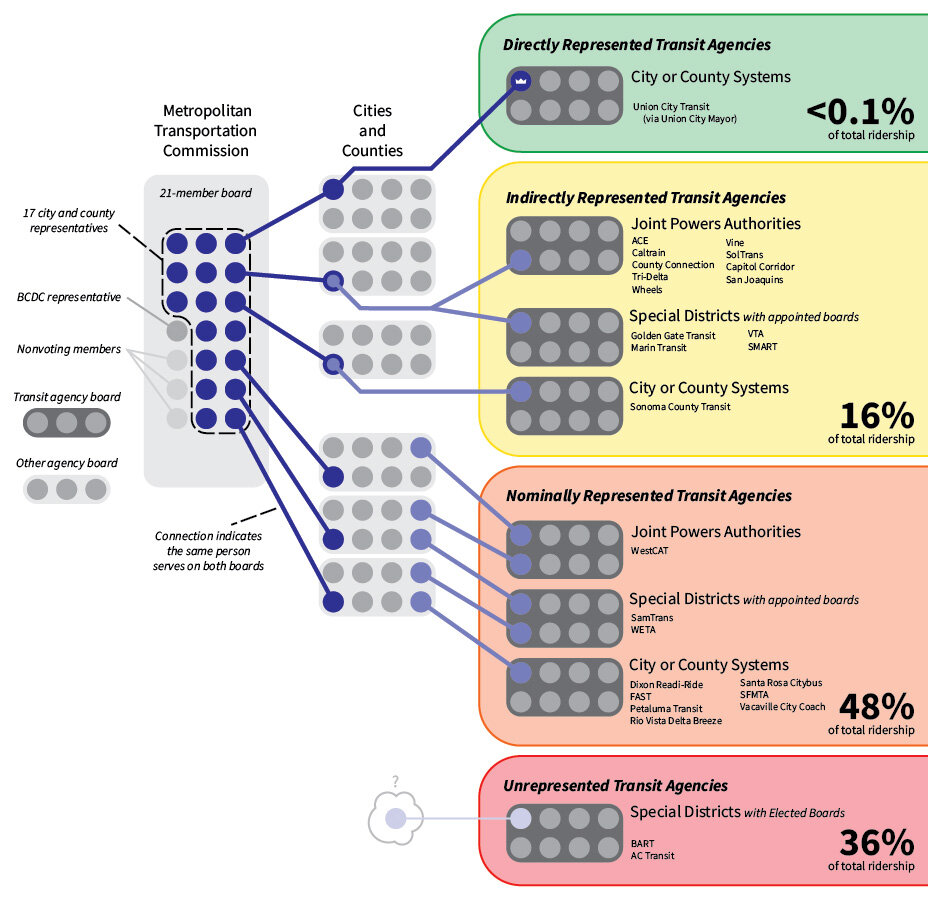

Complicating things further, there are many types of public entities that run Bay Area transit -- special transit districts, joint powers agreements, and agencies run by municipalities -- most of which don’t have a clearly defined relationship with MTC. For example, BART and AC Transit have directly elected boards and have no direct or even indirect representation on MTC - the result is that policies developed by MTC are often not seen as responsive or even legitimate to AC Transit and BART. The following diagrams visualize just how indirect many transit agencies' relationship is to MTC.

The overlap of mandates between MTC and transit agencies has meant that MTC has primarily tried to convince transit agencies to voluntarily coordinate fares and service, setting up forums like the Clipper Executive board and the long defunct “transit coordinating council” but with limited success. Despite MTC’s ability - in fact, it’s mandate - to withhold funds to require coordination of fares and service, in our research, it has never done so. The reason why is likely connected to the second structural problem with MTC.

Problem 2: MTC’s board composition overrepresents local interests and issues and underrepresents shared regional interests.

The way MTC carries out - or, often does not carry out - its mandate is dependent upon the individuals that actually sit on the Commission, and what those people’s interests and priorities are. Experts interviewed by Seamless Bay Area consistently observed that the particular makeup of the Commission - which is established in State legislation - has a significant impact on the agency’s decisionmaking, and favors local projects and programs over policies that benefit the region as a whole.

17 of MTC’s 18 voting members are locally elected officials whose primary responsibility is to just one of the Bay Area nine counties or 101 cities. Most of these officials are actually only even elected within one district of one city or county, making their local focus even narrower. Only one voting member, appointed by BCDC, represents the region as a whole. The three MTC Commissioners that represent broader statewide or national interests (one each representing HUD, CalSTA, and USDOT) are non-voting members and, based on Seamless Bay Area’s observations in recent years, have tended to be among the less vocal members of MTC.

Many of the elected official MTC commissioners also sit on one or more local transit agency boards, which have a closer affiliation to the constituencies these members were elected to serve. While there are always a few vocal “regionalist” champions that do sit on MTC, historically they have been the minority. In some cases, when local elected officials have voted for policies that are in the region’s best interest but that face local opposition, they have been punished.

The resulting dynamic is one where many issues before the MTC are viewed through a narrow local lens rather than a broad regional one. When it comes to getting 27 transit agencies to do something the same way, MTC commissioners must balance their desire for regional coordination with the role they may play on their local transit agency board. Considering the main tool MTC has available to exercise its authority is to attach strings to local transportation funds, it’s not surprising that MTC never exercises this authority. Why would a local elected official appointed to MTC vote to attach strings to funding to a local agency on which that local official also sits? They would be putting a target on their own back, possibly jeopardizing a future appointment to MTC or other commissions for which they need their peers’ support.

Compare MTC’s highly localist governance structure with that of many effective network managers in other parts of the US and the world, which often include a balance of regional or state decisionmakers alongside local ones:

The ATL, greater Atlanta’s network manager created by state legislation in 2018, has a governing board of 15 voting members, with five representatives appointed by the state who represent the 13-county region as a whole. The chair is appointed by the Governor, and the lieutenant governor and speaker each appoint two representatives. Local interests are represented by ten board members who represent ten transit districts covering the entire region, most of whom are not elected officials.

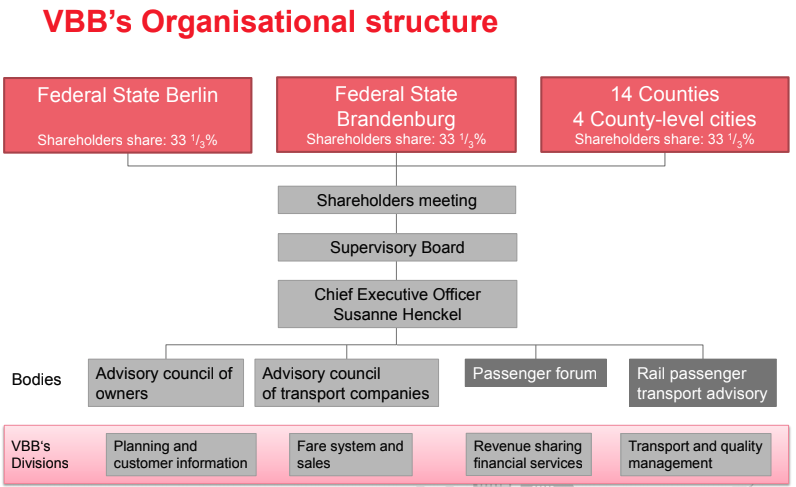

In the governing structures of transit network managers in regions across Germany, Switzerland, and Austria (also known as verkehrsverbünde), state governments play a more active role. For example, as shown in the following organization chart, Greater Berlin’s network manager, VBB, is governed ⅓ by the State of Berlin (3.5m), ⅓ by the State of Brandenburg (2.5m), and ⅓ by the Counties and Cities across the two states.

The network managers of Greater Sydney (Transport for New South Wales) and Greater Toronto (Metrolinx), Greater Boston (MassDOT), and Greater Perth (Transperth) are in fact divisions of state or provincial governments.

The governance structure of Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB), the network manager for Greater Berlin’s transit system, includes representation from the 14 counties and 4 cities within the region, alongside a strong role for the two states VBB covers, Brandenburg and Berlin. VBB also has a “Supervisory board” that directly oversees the CEO; an administrative level of governance that generally doesn’t exist in US transit agencies or at MTC.

For MTC to be willing to exercise its full authority to require alignment of Bay Area transit service standards, more regionalist voices on its commission are needed - something difficult to achieve when the primary responsibility of almost every member of its commission is to represent only a tiny sliver of the Bay Area.

Problem 3: MTC policies are shaped too heavily by boards and committees that don’t have enough relevant technical expertise, and are insufficiently informed by best practices and professional experts.

A third, related problem with MTC that prevents it from being an effective network manager is an excessive reliance on political boards and committees for all kinds of decision making, and the relative under-use of technocratic decision-making bodies made up of experienced professionals to guide important policy. This is also a challenge at many other Bay Area transit and government agencies.

A key principle in the German verkehrsverbund model is the separation of political responsibilities from management/administration responsibilities. Having politicians involved at the highest level of decision-making is essential to ensure accountability and transparency, particularly when it comes to approving funding. Tamim Raad, a Canadian transit governance expert who presented at a recent SPUR and Seamless Bay Area forum, helpfully distinguished between the types of decisions that need to be made by transportation authorities, and what level of involvement from elected boards is needed to ensure public accountability.

A summary of transit agency accountabilities and the relative importance of having elected officials involved in each decision, from Tamim Raad’s presentation at the September 2020 SPUR/Seamless Bay Area webinar Transit Governance: Lessons for the Bay Area.

Very few elected officials who sit on transit agency boards or MTC have a professional background in transportation or public transit. Yet, at MTC and other agencies, elected officials are regularly invited to provide staff direction on administrative and highly technical matters, like contracting, facility design, schedules, routes, fare products, or marketing initiatives. In any given month across the Bay Area, there are literally hundreds of board and committee meetings of transit agency elected officials. The full MTC commission meets once a month; when committees are added, most MTC commissioners are in meetings 2-3 times per month. Many transit agency boards meet even more often; BART and AC Transit meet every two weeks, not including additional committee meetings.

While there’s an abundance of opportunities for elected officials to weigh in on policy, most transit agencies, including MTC, lack robust deliberative decision-making structures guided by technical experts not aligned with a particular agency or geography who could provide very useful feedback for key operational and administrative decisions. Too often, following the direction of political leaders, staff pursue custom, bespoke projects and programs rather than identifying and adopting standards and best practices.

By contrast, impartial technical experts serve a more influential and central role in transportation decision making within other regions, and elected officials a lesser role. Massachussett’s Fiscal Management Control Board (FMCB), established in 2015 to overhaul the MBTA, designates seats for non-elected experts in transportation finance and operations. Transport for London’s board is chaired by the Mayor of London, but is mostly made up of a range of professionals across a range of business, labor, and non-profit sectors. Translink, the network manager for Greater Vancouver, has a two-tiered board structure where the upper-tier board is made up of the 18-mayors of the region, which oversees major budget and policy issues; however other administration and management is overseen by a Board of Directors with relevant professional backgrounds and experience.

When it comes to carrying out the role of a network manager, the lack of technical expertise anywhere in MTC’s formal decision-making structure reinforces the view held by many that it makes decisions primarily based on political considerations. It’s yet another reason why MTC both lacks legitimacy among transit agencies to make good decisions about transit, and hasn’t prioritized regional standards that could significantly improve network integration.

--

Having identified these three problems that prevent MTC from being an effective network manager, the obvious next question is, “what would need to change for the Bay Area to have a network manager?”

Problem #1 suggests that changes to MTC’s mandate alone won’t solve the problem - and the numerous failed past attempts have proven. Without also addressing the responsibilities and structures of 27 other independent agencies, MTC is unlikely to succeed as a network manager.

Problem #2 suggests that an effective network manager should have a governance structure that includes voices who can speak up for all Bay Area transit riders, and the region as a whole, and not just local slivers of the Bay Area.

Resolving problem #3 suggests that a network manager’s governance should carefully balance the role of elected officials and technical experts in decision-making structures.

Stay tuned for our next blog post in early 2021 where we’ll apply these lessons to evaluate at least two potential options for a Bay Area network manager structure.