Making Transit Work for Essential Travel

Reflections from interviews with essential travelers during the pandemic and opportunities for transformational change

While COVID-19 has meant working remotely for many in the Bay Area, tens of thousands of residents still use public transit every week. These travelers depend on transit agencies facing strained budgets and massive service cuts and may face additional risk of COVID infection through their travels and other duties. The burden of having to travel for work on transit puts certain people and communities at greater risk. In California, Black and Latinx residents are most likely not to be able to work from home, meaning this risk is placed disproportionately on these households. Understanding the needs of essential travelers riding transit is thus a racial justice issue that demands research and policy attention.

At the same time, transit trips for essential work impact entire regions and economies, even those privileged enough to choose if they take transit right now.A leading transportation professional, Tamika Butler recently argued:

We have to get out of a mindset where there are only certain people who are transit-dependent. Because we are all dependent on the people who are transit-dependent. So, we’re all transit-dependent.

Essential travel on transit affects everyone. This motivated us to gather experiences from essential travelers during the pandemic to determine what is working and isn’t working in the Bay Area. In December, we presented the findings in a webinar where we discuss the experiences and needs of essential travelers. Our goal is to help transit agencies better serve their constituents as we emerge from the pandemic.

Who is an essential traveler?

We struggled with defining the “essential worker” for this project. This is because traditional definitions — which mostly focus on commute trips — did not reflect the diversity of critical travel that people need to accomplish during this pandemic. Rather than just talking to frontline and healthcare workers, we were also interested in speaking with people who need to take any trip in order to protect their own livelihoods or to care for loved ones. With this in mind, we opted for a broader definition of “essential travel.” Essential travel is any travel to work, in order to protect one’s own livelihood, or to care for loved ones.

We wanted to understand how essential travel was happening around the region and what could improve this experience. We conducted our research in two steps:

Initial interviews with Bay Area transportation agencies and advocates; and

Journey mapping of essential travelers.

Interviews with stakeholders and transportation advocates

A map of the agencies, nonprofits, and advocacy groups we spoke to in the Bay Area.

We started by speaking with stakeholders and advocates from a dozen different public agencies, nonprofits, and advocacy groups. This gave us an understanding of the primary issues that they were aware of and also a sense of the ways in which the pandemic has changed the experience of traveling.

We heard about perennial topics for the region like full fare integration, diversifying transit revenue streams, and equitable fare schemes plus topics related directly to the pandemic. Empty transit stops and infrequent service, both of which create personal safety concerns, were also major topics in our interviews with essential travelers; we also discussed ideas of private cars being utilized by some that could afford to purchase them as filling the gap that transit service cuts create, and the strain on a regional system when it has to create a single, comprehensive public health response when it comes to best practices for disinfection, personal protective equipment (PPE), and physical distancing that does not lead to confusion for transit operators or riders.

These early interviews helped give us an idea of what questions we needed to ask, and reinforced the importance of us talking directly to essential travelers.

Journey mapping: Hearing and learning directly from essential travelers

We utilized journey mapping, an in-depth interview method that is pivotal in human-centered design, focused on centering the user experience. Journey mapping allows teams to work quickly and in non-linear ways to gain insights. The traditional idea behind this method is to think through a user’s (or rider’s) end-to-end experience, their journey through the product. This could be from downloading an app to making a purchase with it; for us, it was the experience travelers had navigating the Bay Area’s transportation network, from leaving their home to making it to their destination.

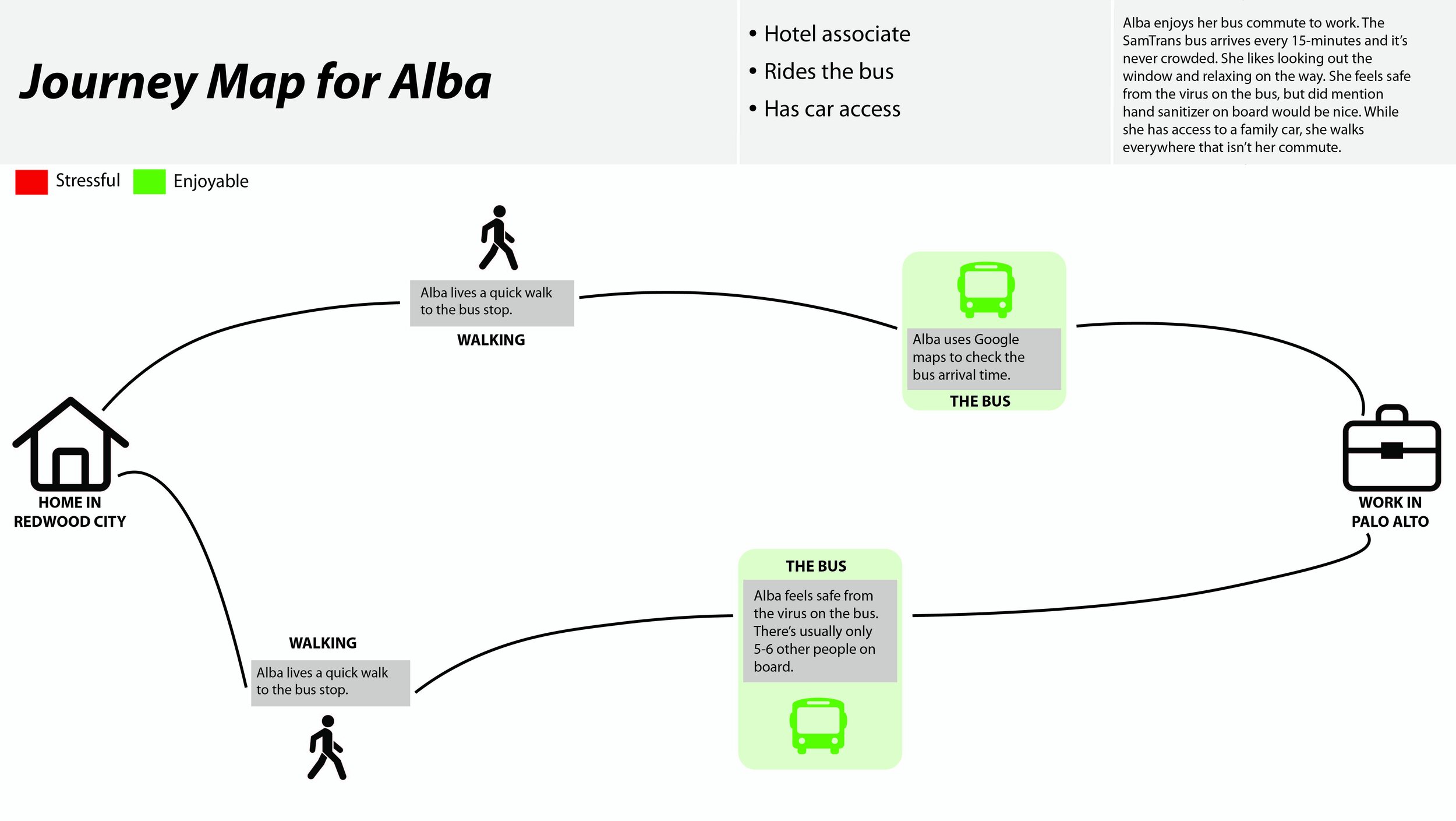

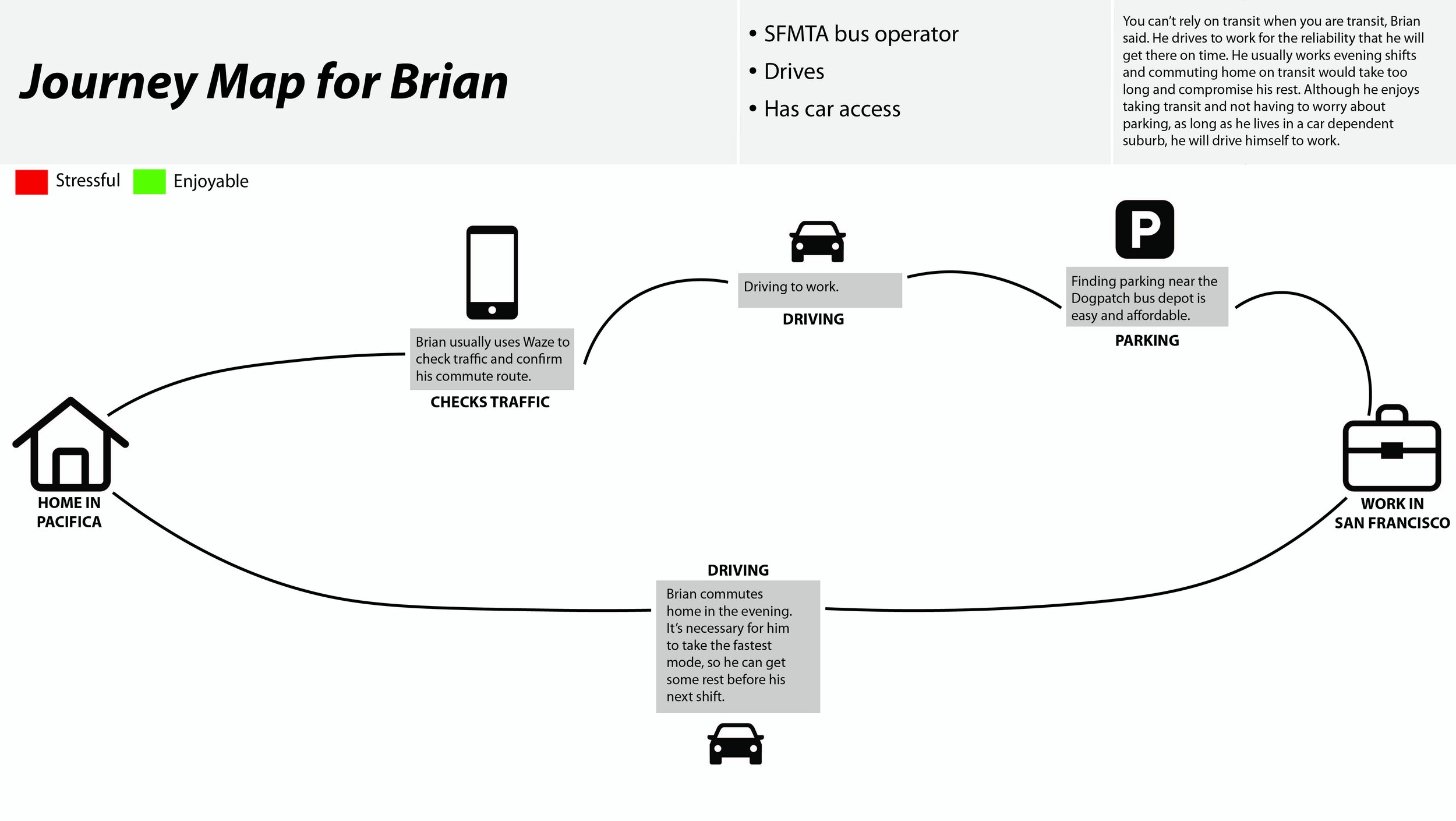

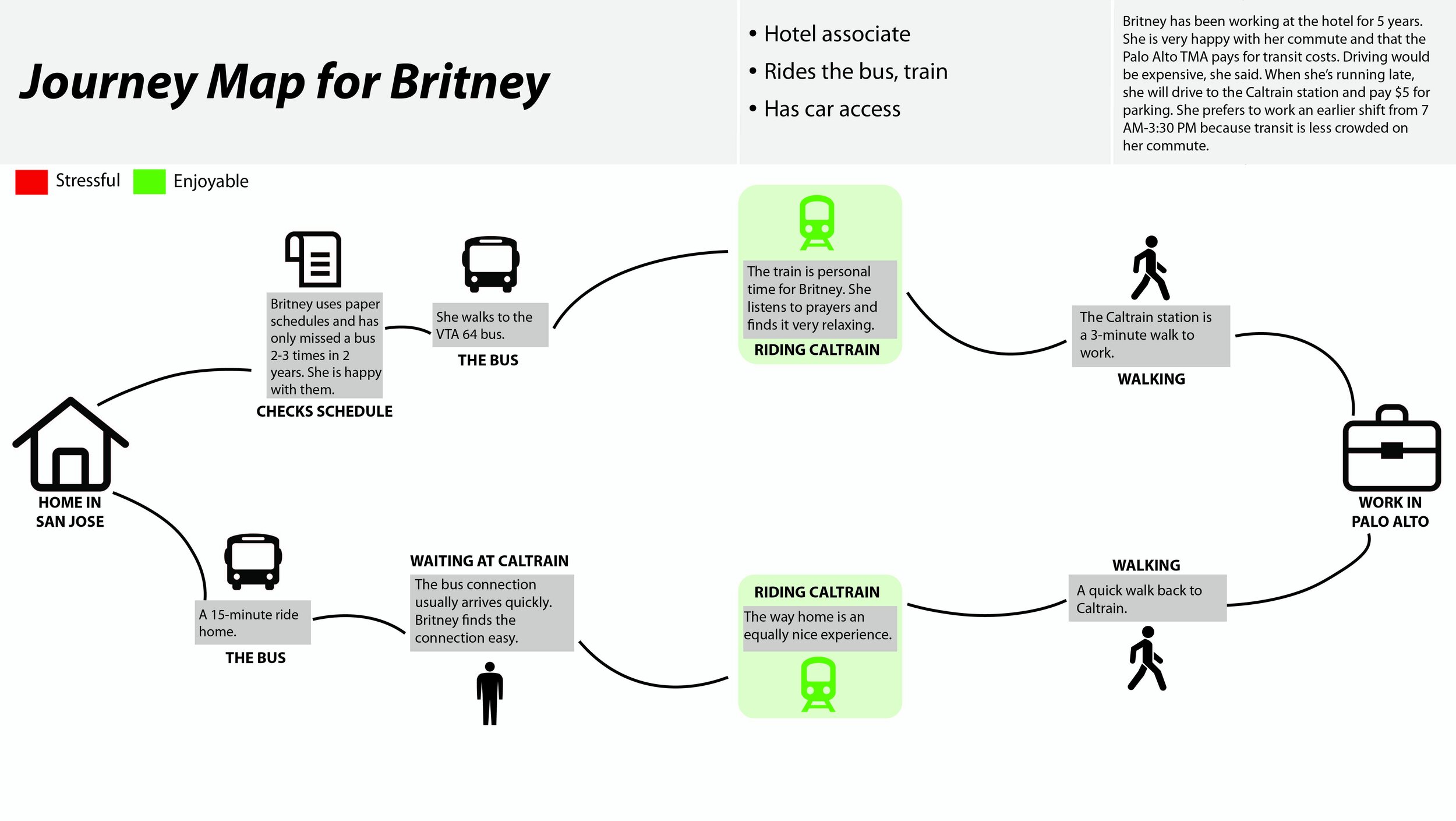

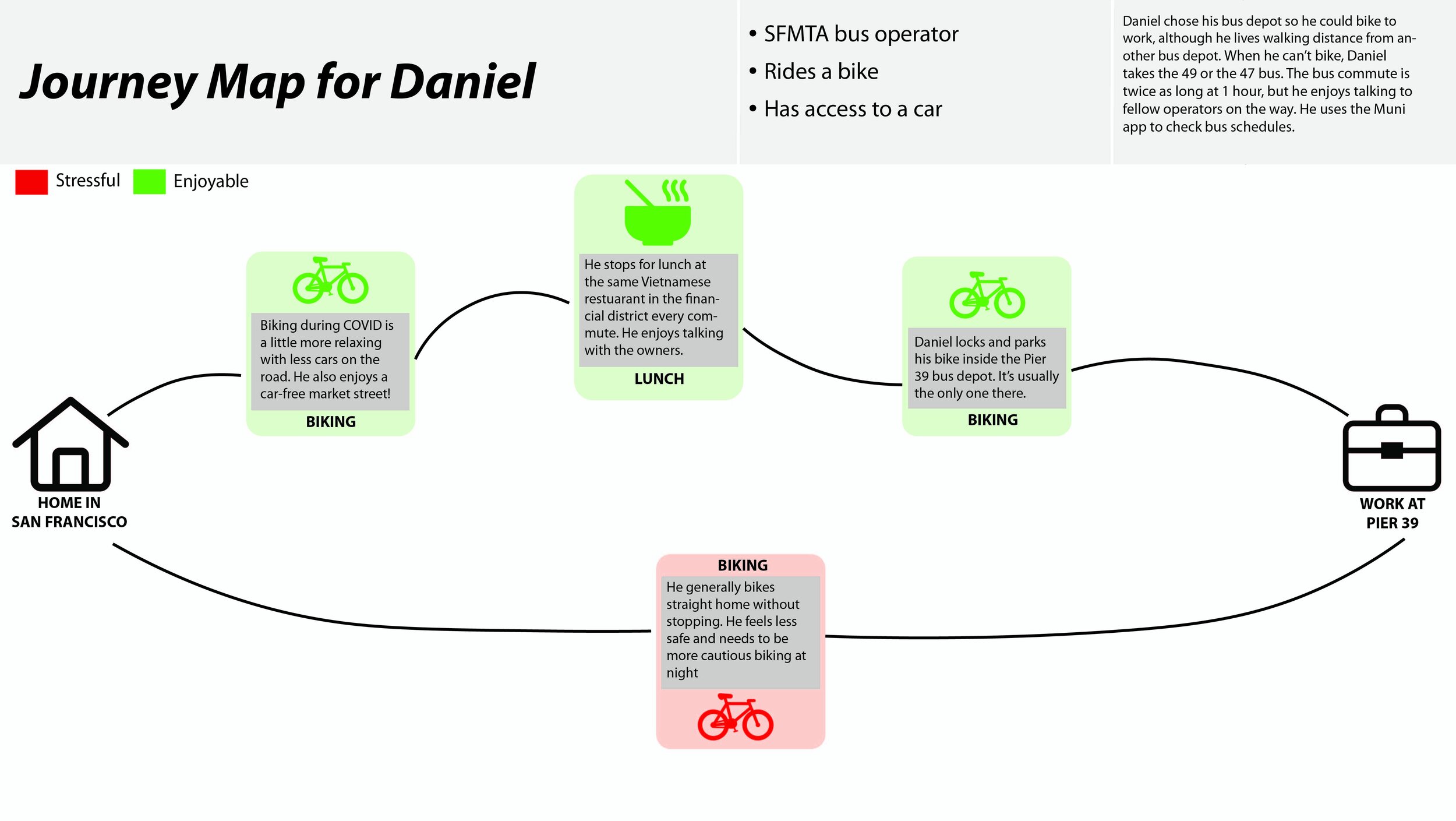

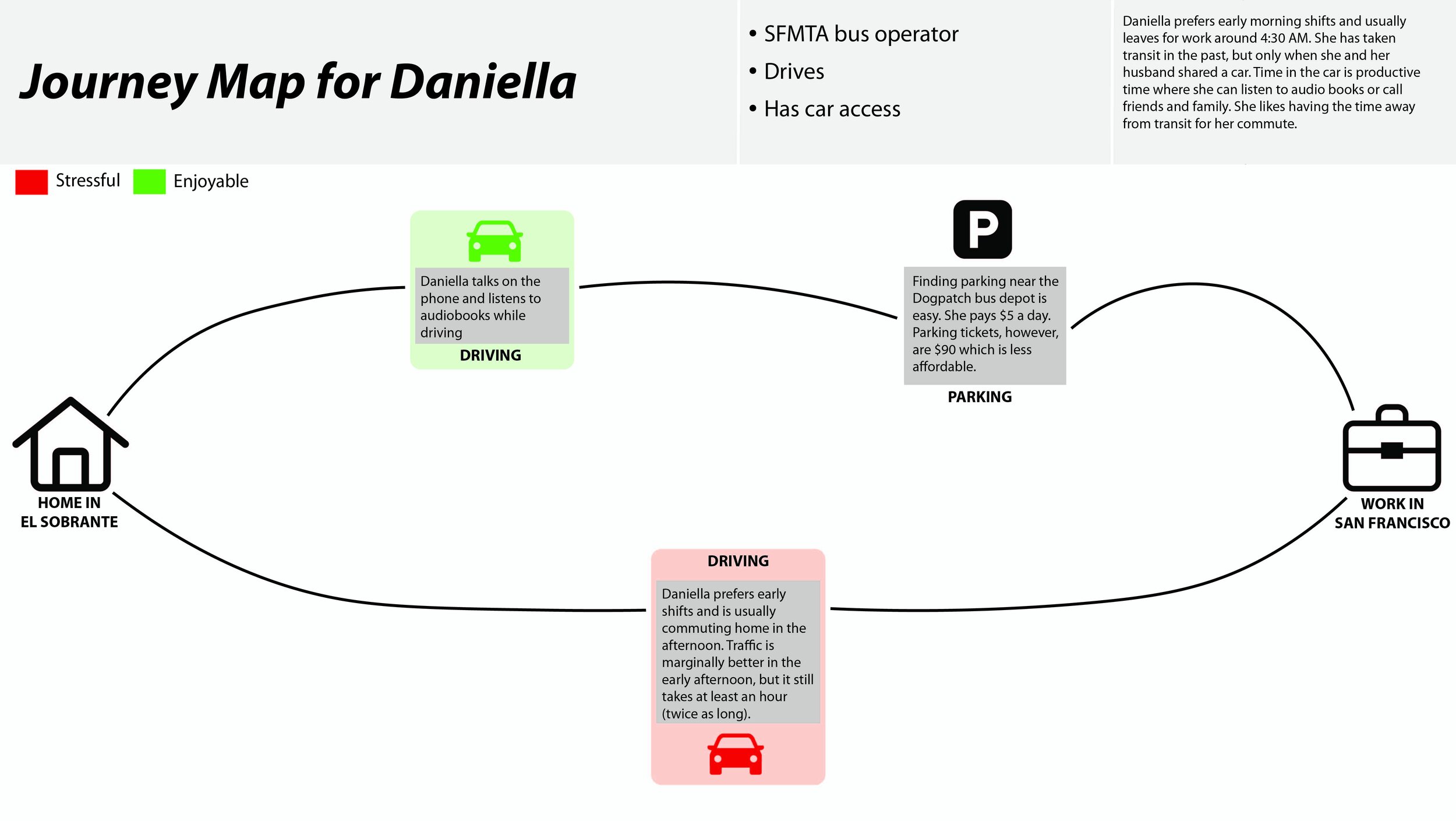

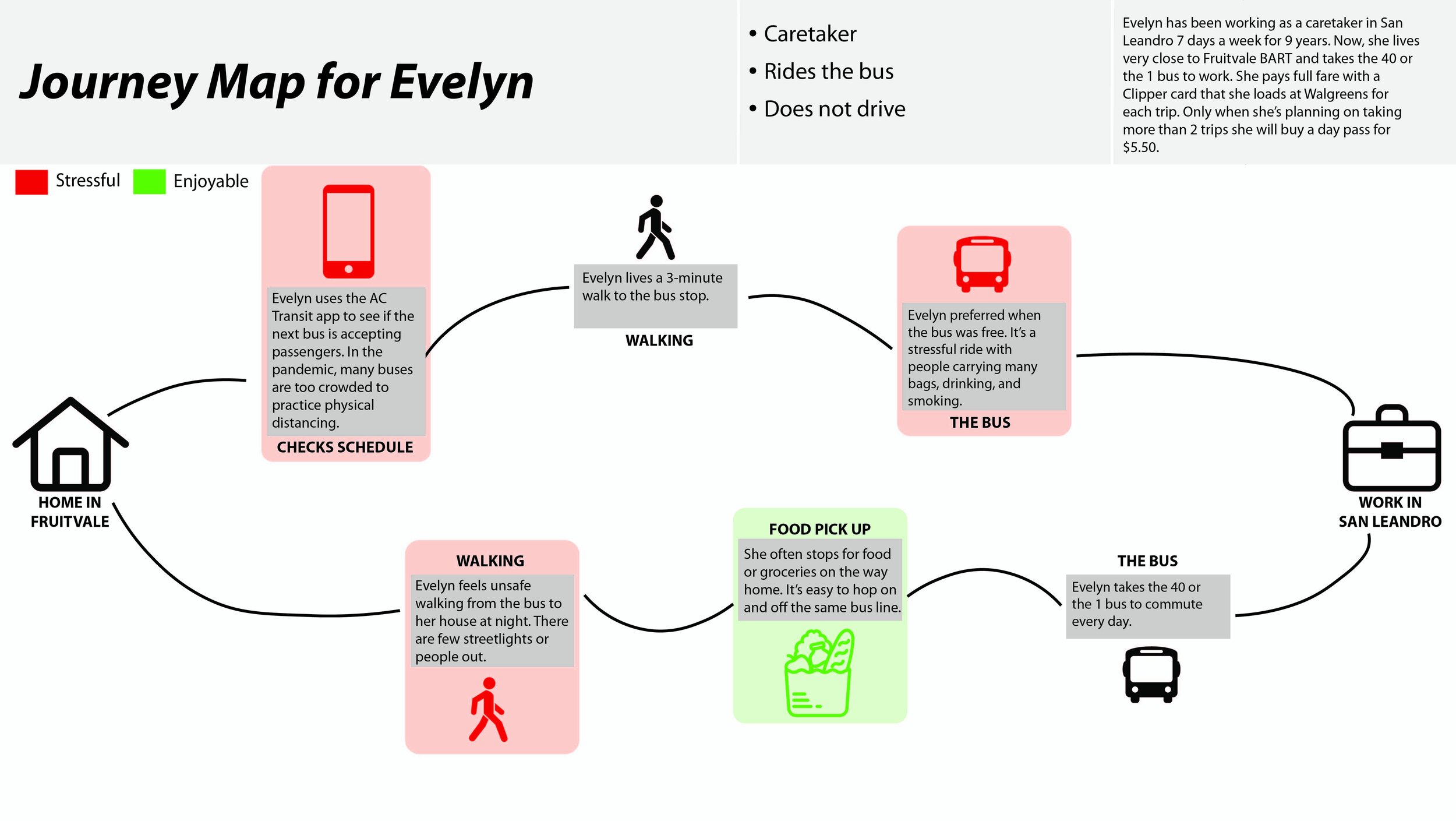

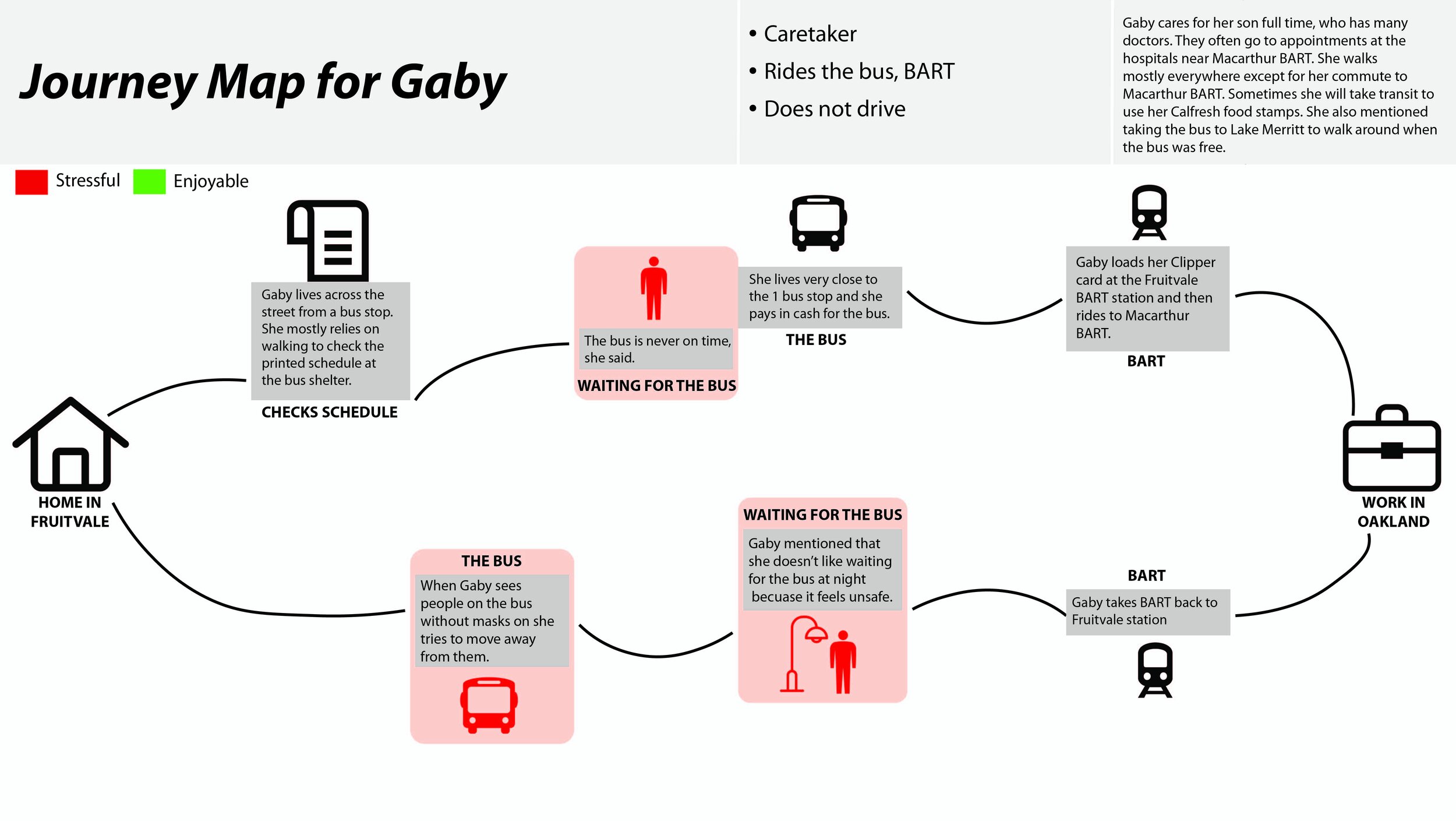

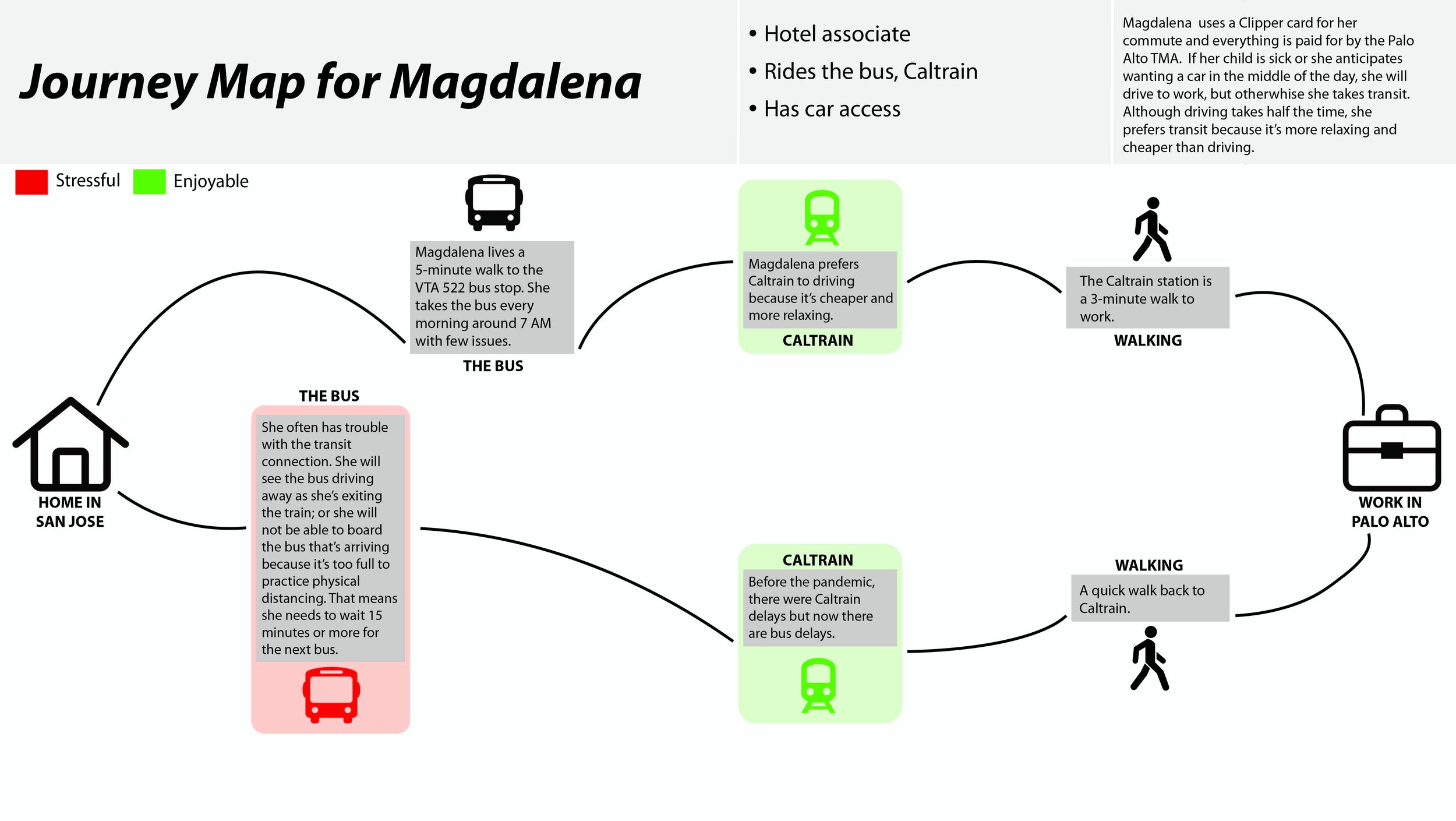

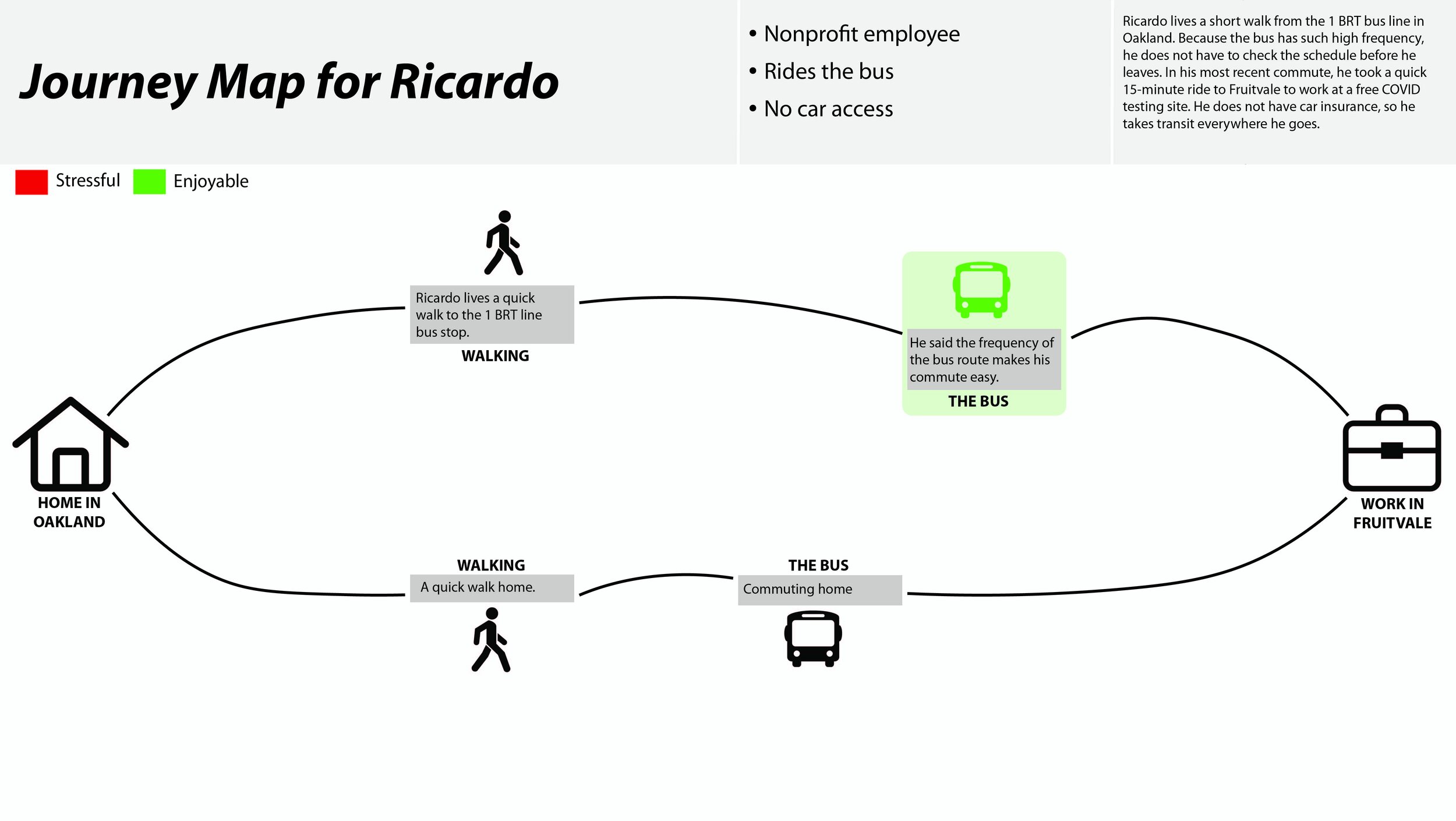

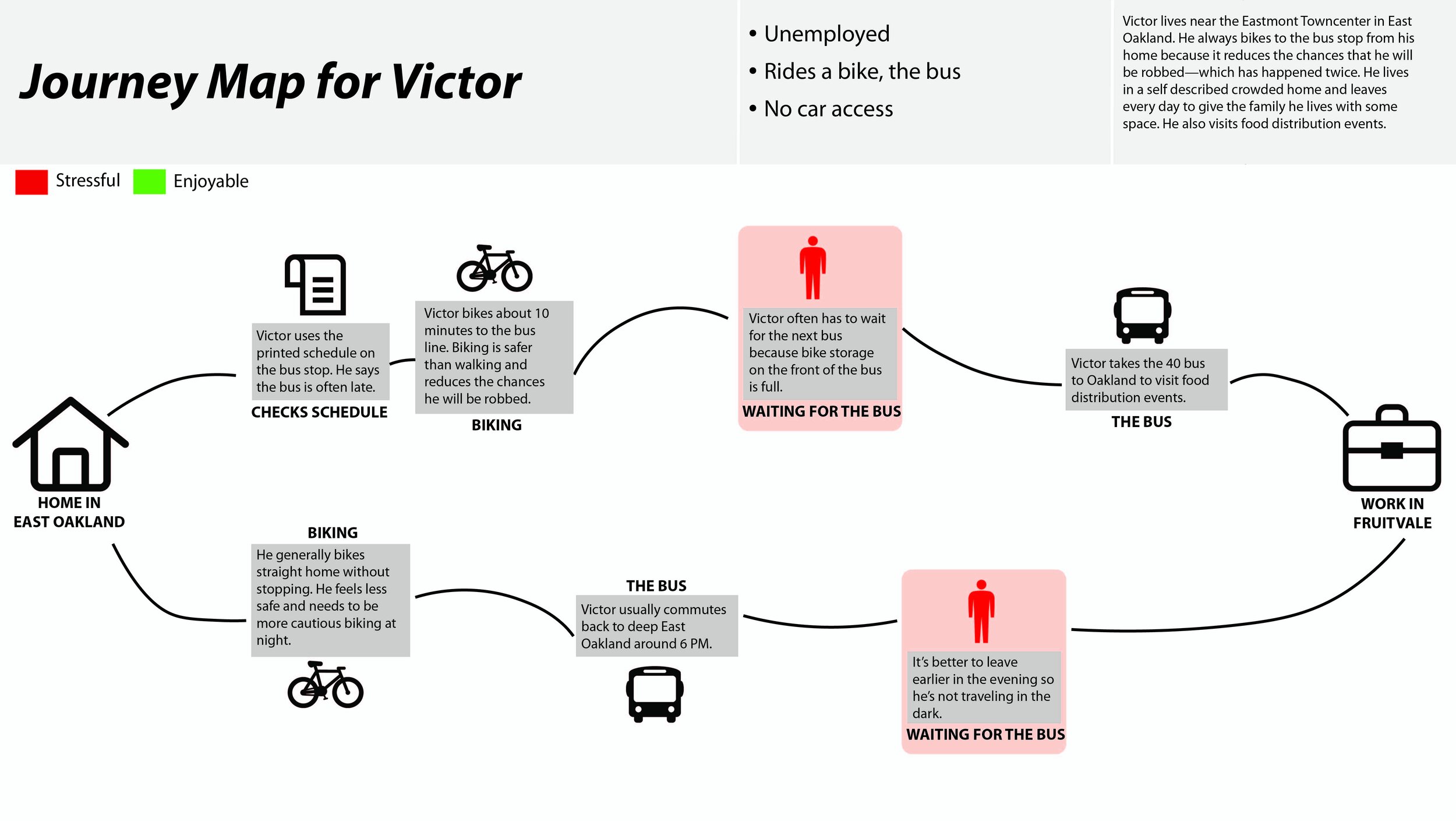

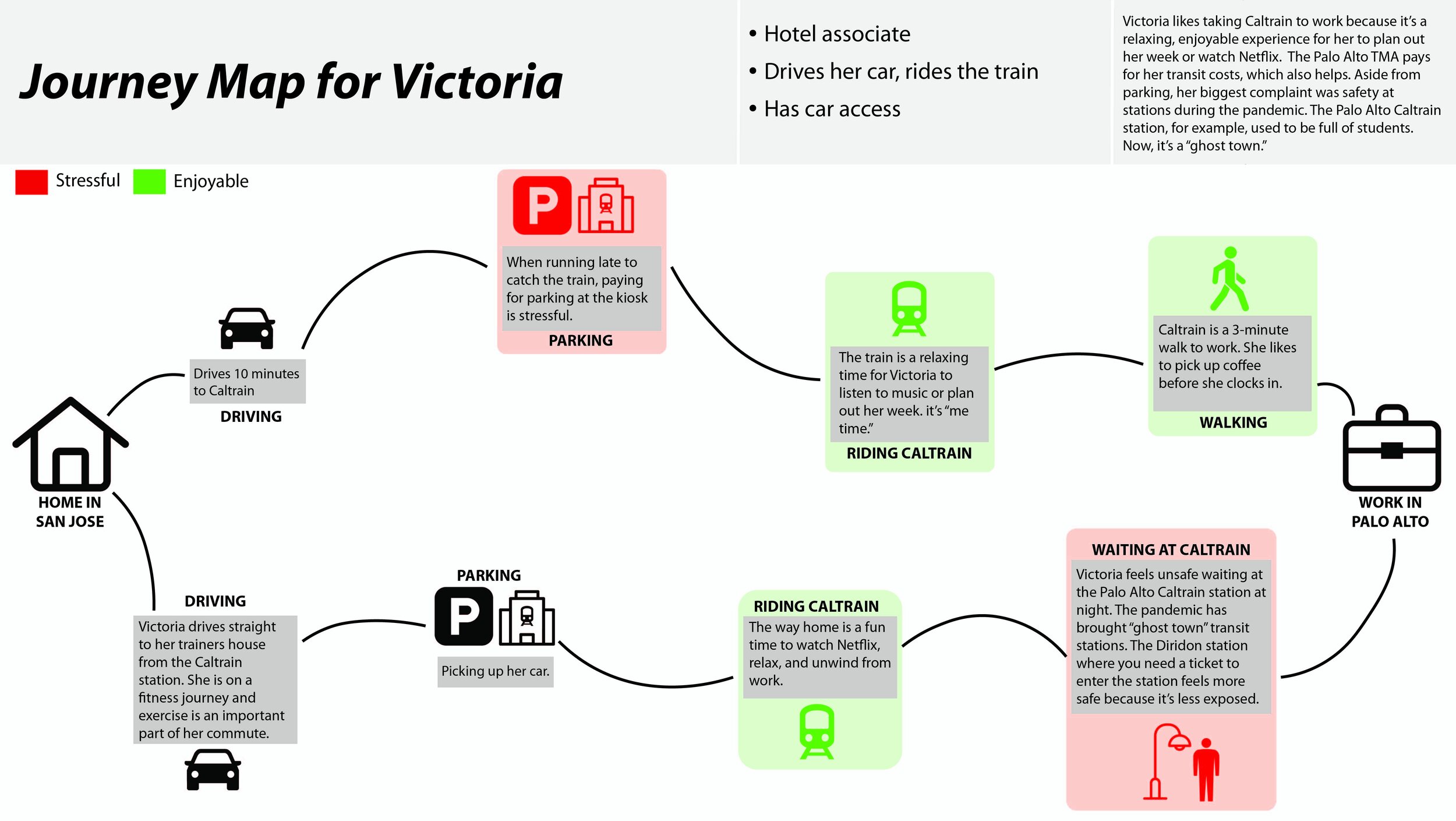

An example of an early sketching workshop using Google Jamboards of an essential traveler’s journey map. The end-to-end trip is split into segments, and then actions are grouped alongside what the person was feeling at that point. We also wrote out motivations around their trip to understand why they took certain routes or modes along the way. The names of the travelers have been changed for anonymity.

This qualitative research method allowed us to capture nuances that can only be uncovered by listening to the individual stories.

We interviewed 11 essential travelers in the region in English and Spanish to map their commutes and understand the highs and lows along the way (see all 11 Journey Maps at the bottom of the page). By talking to riders from around the region, we uncovered some commonalities with issues in the region, and brainstormed potential ways of addressing those friction points.

A geographic representation of the journeys investigated during the interviews.

By understanding each action a traveler takes along each segment of the trip, we could ask questions about what motivates them during each segment, understanding what parts they like, didn’t like, or chose to change to make things easier for themselves. For example, why does the person prefer to commute early? Is it because by choosing early shifts they have a more enjoyable, less crowded commute home in the afternoon? Or is it possibly safety concerns, such as not wanting to wait for a bus alone after dark? While we focused on transit riders, we also spoke with drivers and a cyclist to understand commute motivations and why some chose driving over transit.

With a short project timeline, we view this research as exploratory. There are a few limitations that could be addressed with more interviews. It was important for us to compensate our journey map interviewees ($25 per conversation), but with a limited budget and time (about 30 minutes with each person), we had a relatively small sample size of 11 people. We also did not focus on collecting demographic data from our interviewees.

After our interviews we synthesized the conversations into common pain points and feelings during essential travel. While the project scope did not include development of specific recommendations or funding sources, we include ideas suggested by essential travelers and solutions we would have liked to explore further with a longer project timeline.

Bay Area transit is unreliable

There is a perception that transit is unreliable. Multiple riders mentioned using printed schedules to plan their commute and were often frustrated when the bus was running late, so apps that provide real-time bus location are not helpful for them. Similarly, many faced reliability challenges because buses often are not accepting passengers to maintain physical distance on the vehicles, causing travelers to wait for multiple buses. One of the people we talked to mentioned that she uses the AC Transit app to see if the upcoming buses are too full to accept passengers. Unfortunately this app does not indicate whether bicycle storage on buses is full as this was expressed as a concern as well. Finally, lack of coordination between agencies was often cited as a factor that greatly decreased transit reliability.

Further research is required to understand why users are relying on printed schedules rather than real-time transit arrival information through apps. Increased frequency would likely reduce wait times at transit stops and reduce the perception of unreliability.This would also reduce other issues like seat and bike capacity constraints, delays, and even “ghost town” stations, a term our interviewees used or invoked in imagery and feeling. To mitigate lack of coordination, a regional transit network operator could better synchronize schedules as well.

Transit can be a relaxing, enjoyable experience

While traveling, transit riders value the freedom to close their eyes and relax, watch TV, or listen to music or prayers. It also offers the opportunity to get work done, which isn’t possible while driving.

This could create a unique opportunity for the Bay Area to create an identity around enjoyable transit commutes. Instead of wasting precious time stuck in traffic, essential travelers can get things done while riding transit, or use it as a chance to unwind. A marketing campaign to create a positive identity around being a transit rider could be low-hanging fruit when it comes to regional coordination and budgetary constraints, while helping to entice riders to switch to transit.

“Riding BART, when I first did that was really liberating, to realize I wasn’t going to have to look for parking or worry about whether my car was safe.”

Low income riders really value free transit

Low income riders really valued the bus when it was free, and the East Oakland residents we spoke to were frustrated when AC Transit started charging fares again. Muni bus drivers also commented on how seemingly low-income riders struggled to pay more often, even pre-pandemic, and they wished transit could be free. Transportation fares impose a bigger burden on low income people, particularly during the pandemic, is disappointing, but not surprising. The surprising finding was that one East Oakland rider mentioned taking additional leisure trips, like a walk around Lake Merritt, when AC Transit was free; thus, free transit has the potential to induce more travel–even beneficial travel for one’s health, social activities in addition to potentially spurring additional economic activity through these bonus trips.

A regional subsidized transit pass for low-income riders is a promising solution. A program similar to the Palo Alto TMA (a nonprofit that provides free transit passes to low-income commuters through fees collected from parking) could increase transit use and reduce cost burden. When speaking with the transit riders who have transit passes subsidized by the Palo Alto TMA, they were very grateful for the transit pass; we even found they were less critical of transit, compared to other interviewees. For a region with 27 different transit agencies, providing streamlined fares when riders connect between agencies could alleviate the penalty they would normally incur by taking multiple agencies in a single trip. This along with fare-capping in general, so a rider knows the maximum for a ride they would ever have to pay, could benefit the region. Seamless’s Integrated fare vision could address these concerns by ensuring all agencies offer low-income discounts and fare-capping, and remove transfer penalties.

Paying for public transit is too complicated

Riders we spoke to were over-paying for transit and not aware of all the different fare products or payment methods available to them. One rider we met at a food distribution event was taking AC Transit twice a day every day and paying individually for each ride instead of saving on a monthly pass. Another rider was paying for BART with a Clipper card, but paid in cash for the bus. Using a Clipper card offers a $0.25 discount per ride, which for one of our riders would be over $3 in savings every week. This is a pattern of agencies not reaching riders with the best deal, especially those making essential trips.

Several large Bay Area transit operators, most notably those with significant bus networks, like Muni, VTA, and SamTrans, have observed less use of Clipper Card for payment during the pandemic. More research needs to be done to reach transit riders paying in cash so they are not missing out on fare discounts.

In regards to paying for parking, one interviewee mentioned that the most stressful part of her commute is when she must stop to pay for parking at a kiosk at a Caltrain station, which is frustrating when running late for a train. She was not using the Caltrain mobile app to pay for parking.

It’s difficult to know exactly why users are over-paying for transit or not utilizing available app features for parking. We suggest further research, surveys, and marketing for agencies to improve communications around transit pass programs, rates, and mobile apps — with an ultimate goal of accessible pricing and information about fares. Although every system has people slip through the cracks, we were struck that even in our small sample size of 11, we found people over-paying.

“Ghost town” transit stations

With transit ridership at unprecedented lows due to the pandemic, riders expressed concerns about “ghost town” stations. Essential travelers are often alone, igniting safety and security concerns. Furthermore, with decreased transit service and less reliability, riders have to spend more time waiting for transit. Late buses increase the amount of time riders perceived they could be robbed or assaulted at a transit stop.

More frequent service which would limit the time riders are alone on the platform. Interviewees also mentioned that enhancing lighting at and around transit stops would help to make them feel safer. This would involve coordination with other public agencies. A solution not mentioned that is important is community visioning for new public safety approaches that follow principles from abolitionist planning, echoing the calls of hundreds of planners who this year signed a letter to defund the police.

“I try not to take the train at night now. It [Palo Alto Caltrain station] felt safe when all the students were there but now feels more like a ghost town.”

Concern for catching the Coronavirus on transit varied across agencies

Some riders, most notably those who used Caltrain, did not cite concerns about COVID exposure while on transit. This may be because we did our interviews in October, when infection rates were lower and the Bay Area and so concerns about the virus may have been less than at the end of 2020. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Authority (SFMTA) bus operators, however, cited concerns of catching the virus, as did riders in East Oakland who ride AC Transit. A possible explanation for this discrepancy could be that AC Transit has retained the most ridership of the six largest Bay Area transit agencies throughout the pandemic (averaging 38% of ridership before COVID-19 compared to 11% for BART, for example). This puts a disproportionate burden on AC Transit in the pandemic without more regional coordination. According to Hayley Currier, Policy Advocacy Manager at TransForm:

This plan [Metropolitan Transportation Commission Healthy Transit Plan] still leaves most of the decisions up to each individual operator...asking each operator to come up with their own assessment protocols, determinations of minimum PPE, and job hazard analyses.

Riders mentioned remedies like providing free masks and hand sanitizer on transit. Interviewees from the non-profits we spoke to also said more specific requirements for PPE across all Bay Area transit agencies are needed, which was also a concern for bus operators.

Essential travel beyond the pandemic

Through this research, we have a new list of values and concerns from essential travelers, and we are grateful our interviewees shared their perspectives and feelings with us. This work is just the first step in creating an equitable, racially just, and resilient transportation system in the Bay Area. This work is not meant to yield generalizable findings, but rather to seed important conversations to transform transit and essential travel in the region.

The practice of journey mapping serves as an applicable example for transit agencies and government groups to continue interviewing riders about their trips. We are confident this is a valuable tool to empathize with the rider’s experience and to focus on human-centered design choices in transportation decision making.

The regional magnitude of transit issues is identified in this research as well. Our interviews uncovered many concerns and difficulties essential travelers face every day. Many of these issues relate to our fragmented regional transit system. The astronomical cost of housing and spread of jobs throughout the region necessitates reliable and coordinated regional transit. While we acknowledge that many of our suggested solutions can be expensive and difficult to implement, they would be inefficient if only addressed through with a piecemeal approach.

COVID-19 will not be the last crisis to affect the Bay Area and the burden of these crises should not fall disproportionately on certain groups. As Butler said, essential travel on transit affects us all, regardless of whether we actually use transit, and this will continue even after the pandemic. Transit is essential for equitable, thriving cities and this research supports that crisis response, and transit in general, requires a regional approach and should not wait until the next crisis is on our doorstep.

For more information, download our table of Key Findings and Possible Solutions (PDF) or review all 11 Journey Maps in the image gallery below.

Icon credits: Shaa, Made, i cons, Tamzid Hasan, Mel Haasch, corpus delicti, Sophia Bai, Rihards Gromuls, Dima Lagunov, AFY Studio, Cho Nix, Daniel Behrends, Rahmat Hidayat, Danil Polshin, Nikita Kozin, Ben Davis, Iconographer from the Noun Project

This research was a product of the Department of City and Regional Planning Transportation studio course led by Professor Karen Trapenberg Frick. On behalf of Seamless Bay Area, Eric Eidlin and Sara Barz served as the project “clients” who reviewed and guided the research. The authors can be reached via: kreinhardt@berkeley.edu, andrewtate@berkeley.edu, amythomson@berkeley.edu.