LOSSAN Corridor Resiliency Subcommittee Panelists Propose Groundbreaking Reforms for Iconic Rail Line

In 2025, the LOSSAN Corridor Resiliency Subcommittee brought together panelists from various fields to suggest reforms to the Southern California rail corridor. Headed by Senator Catherine Blakespear (D-Encinitas), the goal of the hearings was to identify opportunities to promote the long-term resiliency, improved service, and increased ridership of the Los Angeles - San Diego - San Luis Obispo (LOSSAN) rail corridor, and determine the reforms needed to drive change.

The LOSSAN Corridor is shared by three passenger rail operators, not to mention the freight services that use the tracks. The corridor has significant challenges. Ridership has been lagging following the pandemic, resulting in challenges to operating budgets. Sections of the corridor near the ocean (such as the Del Mar Bluffs) are facing erosion and require constant closures for repairs.

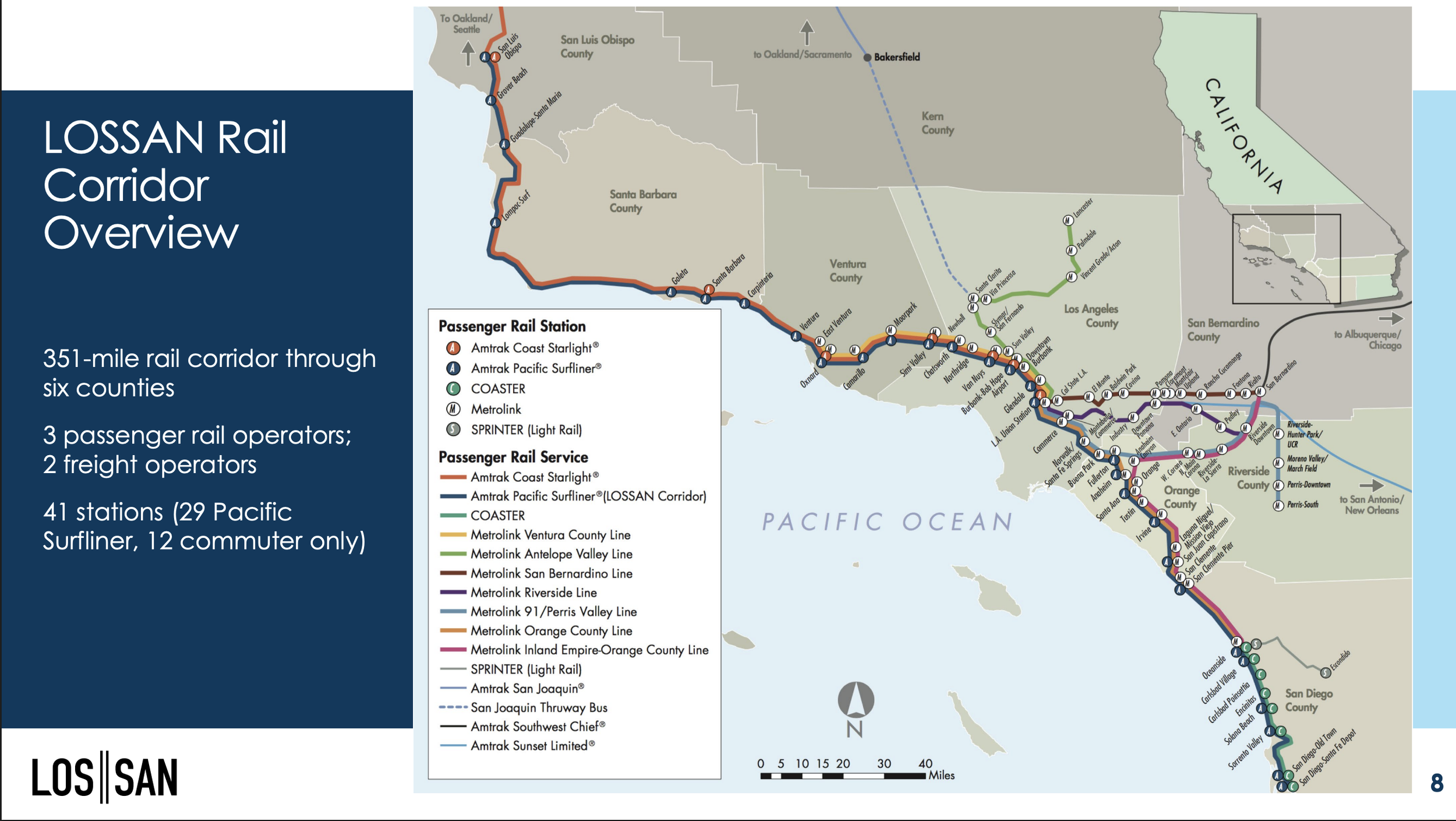

The 351-mile long LOSSAN Rail Corridor stretches from San Luis Obispo in the North to San Diego in the South, covering 6 counties, 3 passenger rail operators, dozens of stations, and 2 freight rail operators (Source: LOSSAN Rail Corridor Agency Overview).

These interrelated problems suggest a need to consider improvements for the corridor as a whole. This subcommittee was formed in response to the requirements of SB 677 and SB 1098 which called for hearings to discuss strategies and programs to fund and prepare the corridor for the future.

The August hearing brought in experts on the field in three areas: Fare and Schedule Coordination; Capital Project Streamlining, and Governance. New ideas were brought up that could bring potentially game-changing reforms to the performance of the corridor.

Fare and Schedule Coordination

Currently, the corridor is served by three distinct passenger rail services: Metrolink (Los Angeles), Pacific Surfliner (OCTA, Caltrans, and Amtrak), and Coaster (San Diego). The current structure of the corridor features overlapping service areas for all three operators, but the agencies offer limited schedule and fare integration, owing to different funding sources and track ownership. Panelists repeatedly observed that the lack of fare and schedule coordination is an inconvenience to customers and a drag on ridership.

According to Genevieve Giuliano of the University of Southern California, “it’s the operators that had the highest farebox recovery ratios that have suffered the most from the drop in ridership because they are so dependent on fare revenue for operations.” Dr. Kari Watkins of UC Davis states that the losses from telework especially affect commuter rail services like Metrolink, so it is high time to rethink the role of transit to attract new types of travelers. It is not enough to keep the existing operating and fare structure as it is. Gillian Gillett of the California Integrated Travel Project (Cal-ITP) also highlighted the urgent need to rethink fare policy to make it easier and more affordable to pay for transit. Examples include giving strategic fare discounts or fare capping, whereby the system will automatically stop charging the user past a certain point equivalent to a weekly or monthly pass.

There is an ongoing effort through CalSTA and Caltrans to coordinate with Capitol Corridor and San Joaquins to form a rail payments alliance to grow ridership and revenue, according to Chad Edison of Caltrans. This could be used to facilitate reservations, seat assignments, multi-operator ticketing, among other features. In the future it could then be possible to extend such an alliance to LOSSAN. Integrating payments would add convenience to riders; this is related but separate from coordinated fare policies with measures such as standard discounts or multi-agency fare caps.

In addition, the ownership of trackage is a patchwork of freight companies and transit agencies, leading to complexities in operating each service. Senator Blakespear mentions the cascade of delays that could happen on passenger services when even freight is delayed, which would inconvenience passengers and not give a favorable impression on its reliability.

In other countries and regions like Seoul in South Korea, the government took a greater role in network planning, with measures including introducing an integrated fare structure. Ridership and revenue grew as a result of the reforms, although they required an increased amount of operating subsidy. Since customers were satisfied, both the public and the government were in overwhelming support of continuing or even increasing said subsidies.

Very recently, Illinois passed a bill which reorganizes the myriad of operators in the greater Chicago region under one “network manager,” allowing for greater fare, schedule, and capital project coordination among the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA), Metra, and Pace.

Capital Project Streamlining

According to a study by the Eno Center, the US pays 50% more to build transit than other countries. The situation in California is even worse, where costs range from 2-3 times the global average cost per mile. The LOSSAN corridor, where key projects have been stalled, is one of many areas where California’s practices lead to high costs and slow timelines.

At the LOSSAN Corridor hearings, experts mentioned several important factors including permitting, environmental review, and public sector capacity to manage the project.

Based on decades old traditions, rail and transit construction in California relies heavily on external consultants. This practice drives up prices, neglects opportunities for efficient standardization, and results in loss of valuable expertise once each project is finished.

Marc Vukcevich, Director of Policy for Streets for All, reading a letter submitted to the committee in partnership with Californians for Electric Rail, urges that to have projects delivered more efficiently and cost effectively, state capacity needs to be built up to retain knowledge and expertise, and not lose this learning to consultants. Philip Plotch of the Eno Center echoes this sentiment, saying that consultants can be valuable to provide specialized knowledge about technically challenging topics, but urges caution on overreliance on them when the agency in question can hire in-house.

Plotch also noted in his presentation that construction costs and timelines are heavily impacted by delays in permitting and environmental review. He says that it would be good for federal and state governments to provide adequate resources to perform these duties in a timely and coordinated manner.

Juan Matute of UCLA also calls out these issues in his remarks on the panel, noting that change will involve tradeoffs. Matute noted that the current environmental review process tries to do something unachievable: “There is no such thing as a major capital project that has no impact on something or someone.”

A recent report published by Californians for Electric Rail entitled “Against Patchwork Funding,” provided examples of projects that increased scope and cost due to accommodations from various stakeholders. The delays compound, escalating the cost of the project.

Senator Blakespear observed that the state has devolved a lot of decision-making to local control deliberately, to increase the responsiveness to needs of local communities. However, this leads to fragmentation that gets in the way of solving larger problems. Blakespear notes that in her district in San Diego, where there is lot of expertise amongst staff, even as they received $300 million from the state 4-5 years ago to plan for the moving of the LOSSAN corridor away from the Del Mar bluffs, they are still doing community outreach for a portion that is only 1.2 miles long, raising concerns about the ability of current governing structures to deliver this project.

The Against Patchwork Funding report observes that the California State Rail Plan lacks concrete steps to fund implementation, does not require plan compliance for funding, and does not provide funding certainty for projects building out the plan. This contributes to slow implementation on projects delivering the State Rail Plan including on the LOSSAN corridor.

In a public comment at the hearing, Streets4All mentioned their letter alongside Californians for Electric Rail, observing that lack of consistent funding leads to poorer quality long term planning, citing the example of the Del Mar tunnel which will potentially not account for electrification.

Lastly, Steve Roberts, the president of the Rail Passenger Association of California, gave a spoken comment on the importance of investing in and delivering capital projects to achieve goals of mode share and revenue by running reliable and frequent service. The longer it takes to deliver capital projects, the longer it takes to reach the state’s goals to reduce vehicle miles travelled. RAILPAC presents the trade-off: keep subsidizing the same service, or invest, deliver, and have increased ridership that will also help with funding.

These issues need to be addressed because the impacts of climate change on the corridor are only increasing (e.g. the need for repair or reconstruction, such as the realignment in San Clemente or the Del Mar bluffs). There is a need for multi-year capital projects to improve the conditions, whether through emergency repairs or longer-term fixes. These capital projects are key to unlocking reliability and improved service, as the corridor currently has rights to run up to 84 passenger trains per day from Los Angeles to Fullerton and then to Riverside and San Diego.

We could say that trust in government is also put in doubt as people find that the funds raised from their taxes cannot deliver transformative projects within budget and on time.

Governance

According to a report by USC, the LOSSAN corridor has strong passenger growth potential and caters to a small but important freight market. Unfortunately, the corridor is hamstrung by a complex patchwork of governance and funding. Rail infrastructure and right of way are owned by multiple entities, each potentially with conflicting interests. Service is also run by operators that perceive themselves as having different objectives. The corridor is under the jurisdiction of multiple planning organizations, which are funded by disparate sources. Lastly, local freight traffic needs to be accommodated in this area. The fragmentation of governance and funding leads to extremely slow progress in things like coordination and capital projects which then leads to a lack of trust in government to do things effectively.

In light of this situation, Caltrans is set to request funding from the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), through its Corridor Identification and Development Program (CIDP), to formulate a LOSSAN Corridor unified service vision for Metrolink, Coaster, and Pacific Surfliner, which will also aim to coordinate with freight railroads. It is anticipated that work on this part of the program will be started by mid-2026, and will identify a pipeline of projects that will advance the vision. In his presentation, Kyle Gradinger of Caltrans mentioned some among the multitude of studies by different bodies including:

Orange County Coastal Rail Resiliency Study, led by OCTA

San Diego LOSSAN Rail Realignment Project, led by SANDAG

Long Term Railroad Adaptation Study, led by the California Coastal Commission

How will all these studies fit into the larger picture of the entire corridor? California’s State Rail Plan brings a service-led planning method to the forefront, citing the European maxim “organization before electronics before concrete,” meaning that clarifying governance and systematic planning should precede investments in infrastructure. However, the governance is fragmented and there is not a systematic plan and design to guide infrastructure investments. Giuliano, in fact, questions in her presentation whether the current governance structure is appropriate to address current challenges on this scale.

Juan Matute from the Institute of Transportation Studies of UCLA challenged the LOSSAN subcommittee to dream big, on the scale of tens of billions of dollars: what would happen, for instance, if the state owned railroads? He points to other states like Virginia and North Carolina that have purchased their railroads. LOSSAN is important to the state both as an economic and a tourism corridor, so such investments could be worthwhile in the long run. To manage such a corridor, he suggests the piloting of a model like in Europe, the Verkehrsunternehmer. He explains it akin to the integrations done under the international air transport association (when it comes to inter-ticketing, luggage coordination), as well as standardization for interoperability, process, and data.

Furthermore, Matute cites the fragmentation of governance as generating conflicting input from various levels without a clear means to balance them. At the state level, there is increased focus on affordability, reliability, and mobility, whereas at the local level, land use and sometimes unrelated local infrastructure needs are at the forefront. When each part of the project needs to be modified to appease a few people in local areas, the costs can quickly add up. Sometimes, the overemphasis of the local concern makes mobility less reliable and affordable, losing the original goal of the project in the first place. There needs to be a balance between the overarching goals of a project and local concern, something that Matute observes is a political question.

This is echoed by Streets4All in public comment, where they call out the parochial system of governance as not working. The highway system, in contrast, does not necessarily consider hyperlocal concerns; instead, it works because it needs to work for the whole state or region.

On a Better Future for the Corridor

Throughout the hearing, Sen. Blakespear reiterated the importance of reliability and frequency as the key tenets of reforming the LOSSAN Corridor. It is at an inflection point as part of rail in Southern California; it is up to legislators, operators, and other parties involved to choose whether to maintain status quo, or choose a different path. The Senator called for the legislature to be “bold, visionary, and ambitious” to bring about reforms that will deliver projects to benefit Californians along the corridor.

The Senator also highlighted the recent reforms done to CEQA, California’s landmark environmental law, to streamline the process for building housing in light of the current crisis in the state. California has thus shown that it has the appetite for reform, as shown in its recent flurry of housing legislation designed to streamline the housing process to address the urgent need for housing.

It is refreshing to see that best practices around the state and internationally were brought up by the panelists for the consideration of the subcommittee. We hope and encourage that ideas for reform raised at the LOSSAN corridor hearings can be put into practice into the corridor to improve its performance for years to come.

Gabriel Fadri is a transportation engineer and transit advocate based in Berkeley.

Sign up here to get our blog posts sent directly to your email.