Notes from Switzerland: New funding and governance reforms together created Zurich's world-class system

VBZ trams in central Zurich, connecting to the Zurich main railway station, operated by SBB.

Switzerland’s world-class transit system, with its plentiful, seamlessly integrated service - including clockface, coordinated timetables and integrated fares - make transit coordination look so easy that one may think it has always been this way. The study delegation of Bay Area transit leaders to Switzerland learned first hand from Swiss experts that what riders experience today is the result of many years of hard work, including concerted advocacy, reforms to institutions, political debate, governance changes - that collectively have contributed to Swiss voters approving ballot measure after ballot measure in support of more investment in the system.

Critically, the Swiss transit turnaround involved both raising more funding for transit and getting governance right, together – establishing a transportation network manager with the mandate to oversee coordination at both the national and regional scales.

As the Bay Area seeks to pass a transformational regional ballot measure in 2026, the lessons of Switzerland’s ‘pivot’ towards seamless transit in the 1980s could not be more timely and relevant. Our study delegation learned about the specific story of greater Zurich, the country’s largest metropolitan area of 1.7m, and also the changes that were also happening at the national level, among the country’s population of roughly 9 million.

Failed ballot measures and the need for a new value proposition to voters

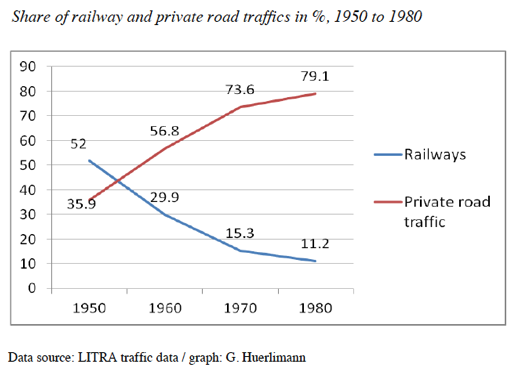

It hasn’t always been sunny times for Swiss transit. From the 1950s to the 1980, transit ridership declined dramatically as car ownership and highways expanded, to the point where by 1980, the share of trips in private automobiles nationally increased dramatically to 80%, while rail trips declined to just 11%.

Amidst declining public transit use, in 1973, Zurich region voters rejected a multi-billion dollar plan for a U-Bahn (subway) system in Zurich. 57% of Zurich canton voters rejected it, including 71% of City of Zurich voters. This came after another defeated plan for an underground light rail system brought to voters in 1962.

Image from proposed U-Bahn system that Zurich voters rejected in 1973.

In rejecting the subway proposal, voters saw a tremendously disruptive and expensive large capital project without a clear benefit for all. The purpose of the project was poorly communicated – and planners and elected leaders were humbled and forced to think deeply about how to move forward amidst poor public sentiment.

While the Zurich region was grappling with the fallout of failing to build a subway network, at the national level, ambitious plans for a high-speed rail networks were also hitting roadblocks. Transportation planners in the late 1960s and 1970s proposed high-speed rail networks like those that had recently opened in Japan. However, public and political sentiment was largely against such plans, which were viewed as serving only a few main large cities rather than the whole country.

As academic Gisela Huerlimann of the University of Zurich explains, policymakers responded by developing a plan for transit service improvements that “consisted of improving the whole railway net[work] instead of concentrating investment onto a set of high speed lines.”.

A coordination-based model overseen by SBB and the federal government

Swiss officials looked abroad for inspiration, and found the ‘Dutch’ pulsed-time table model as an alternative to the Japanese model. Swiss engineers set to work identifying how it could be implemented in Switzerland at a national scale, and found the Dutch model could bring significant benefits for the greater number of people, could be implemented far more affordably than many of the high-speed plans. As a result, the model was more supportable by voters.

SBB, the national rail authority, introduced an initial version of the coordinated timetable on the whole national rail network it controlled, at a 1-hour interval, in 1982, with great public support. The integrated timetable philosophy laid groundwork for the success of the 1987 ballot measure, Rail 2000, that Swiss voters passed enthusiastically “with the integrated fixed interval time table as a guiding principle for planning and investment." (Huerlimann)

Subsequent national ballot measures have been approved by Swiss voters that have steadily expanded investment in public transit and increased frequencies between major hubs to every 30 minutes, or 15 minutes in some cases. The integrated time table, and its effective administration by SBB and the federal government, have been essential to the passing of increasing investment in Swiss public transit over many years.

The “Zurich Model” of Public Transport

In parallel to SBB stepping into the role of the country-wide ‘network manager’, overseeing clockface timetables as a condition of new funding, Zurich region responded to the 1973 ballot measure defeat by also developing a more holistic vision for improved regional transit network that provides benefits for all – consistent with the federal philosophy and what was also going on in Germany.

Regional leaders developed the ‘Zurich Model’ of public transit - mostly at-grade routes based on existing tram and regional rail lines, enhanced by investing in transit priority and reliability measures, alongside centralized network management, coordinated schedules and unified customer experience.

Official from VBZ explaining the evolution of public transit in Zurich to the Bay Area study delegation.

Zurich leaders brought a new vision to voters in 1981 - a proposal for an integrated ‘S-Bahn’ regional rail network – that would be run with integrated timetables and fares, seamlessly connected with the local tram and bus networks. Critically, it called for the creation of ZVV, a new regional authority to manage and integrate Zurich’s regional network seamlessly. The measure passed with 74% support - a dramatic turnaround from the failed measure just eight years prior.

ZVV’s formal authority to coordinate the Zurich region’s entire network was then formalized in a subsequent 1988 ballot measure, approved by 75% of voters. The S-Bahn then opened in 1990, on time – with integrated fares and schedules. As of 1990 ‘the pivot’ of Swiss transit was now complete.

Image from the opening of Zurich’s S-Bahn in 1990 (left); “yes” pamphlet from the 1988 voter initiative to formally create the ZVV, with the campaign slogan “One ticket for the entire canton”

While it’s not the focus of this post, it’s important to note that in the 1990s Zurich was simultaneously struggling with one of Europe’s worst drug crises: open-air drug markets in central Zurich and high levels of drug overdoses. While we don’t know how it impacted transit, it’s a reminder we sometimes need to combat multiple problems at once. For the Bay Area, we need to coordinate and improve public transit - and address drug addiction and crime – we can’t wait on a fix for one before we deal with the other. More information on Zurich’s drug crisis in the 1990s.

Growth in passenger trips on the S Bahn system from its opening in 1990 to 2019. While ridership dropped during the pandemic, in 2023 Swiss officials report they are forecasting a return to 100% pre-pandemic levels of ridership.

Since 1990, when both the S-Bahn opened and ZVV oversaw a fully integrated system of fares and service, the Zurich region has seen dramatic and sustained increases in public transit, and reductions in driving – including a 35% increase in per capita transit trips between 1990 and 2014. Service levels have increased by 75%. The region has created a ‘virtuous cycle’ of increased ridership, and more and more investment. Subsequent ballot measures have brought in more and more funding for new projects and service expansion.

ZVV roles and responsibilities

So what does ZVV do? ZVV’s roles and powers are defined in legislation. ZVV:

collects all fare revenues in the region,

oversees the annual timetabling update process in partnership with local agencies

contracts with its member public transport companies to provide public transport service at a pre-negotiated price, volume, and quality.

oversees other functions, like joint marketing, communications, passenger information, and financing.

The division of the Zurich region into markets, each overseen by one of the eight primary transport operating companies in the Zurich region, with SBB (not shown). ZVV enters into service contracts with operating companies to run specified levels of service in each of these markets.

ZVV doesn’t directly run any service, but works primarily with eight transport companies with ‘market responsibility’ over different parts of Zurich, or in the case regional and interregional service, SBB, to run coordinated timetables, service and fares. There are 37 total companies that belong to ZVV and abide by its rules.

ZVV manages the timetabling updating process, which is every two years. This creates an iterative process between ZVV, which can advance network-wide improvements, and transport companies, which have the opportunity to propose local changes they feel are important. The structured process, with structured milestones month-by month, reconcile local and regional changes into one common timetable that is coordinated for the customer.

ZVV also manages some centralized services on behalf of all transport companies, or in some cases contracts with companies to compete certain functions for the whole regional network. This includes a common security system, including common fare enforcement across all systems.

ZVV oversees customer satisfaction for the network, and closely tracks operator performance, particularly for punctuality, information provided to customers during disruption, cleanliness. Operators may be penalized if they don’t meet certain targets.

Public transport company responsibilities

Our delegation visited not only with ZVV, but also with VBZ, the largest transport company in the region. When we asked VBZ officials if they ever questioned the value of regional coordination with ZVV, they responded that while sometimes there can be disagreements, that all transport companies are committed to the principle of ‘customer first’ and to the system of coordination, because it delivers the best possible results for riders.

Transport companies in Switzerland certainly still have plenty of opportunity to innovate, and are themselves complex organizations with motivated, highly talented staff and board members who make valuable contributions. Transport companies lead their own timetable planning - in coordination with ZVV - and are also the entities with the closest relationships with riders. Most public outreach for service changes, new projects and programs, are led by transport companies, not ZVV.

At the end of the day, public transport companies see it as a shared responsibility to deliver a quality service to riders - and members of VBZ were proud to share their experiences with our foreign delegation.

Summary

The success story of Swiss and Zurich public transit is a story of leadership, commitment to better results, and significant political negotiation among many may actors and levels of government - and the public.

The Swiss government wasn’t able to just raise taxes and fund whatever system they wanted at high levels of service, and worry about reforms later. Quite the opposite - Swiss voters rejected two plans for expansion because they didn't see clear benefits.

Public transit agencies regained trust among the public by beginning to run a highly coordinated, even with limited funding. Then the public made the case to voters to invest in expanding service by showing it had a clear plan that would benefit everyone. Ballot measures that funded a lot of the service increases and capital expansion that makes Swiss transit so plentiful and ubiquitous came with a condition of governance reform to provide accountability, including the creation of ZVV in 1990.

The Bay Area has little choice but to go to the ballot in 2026 with an ambitious regional ballot measure. Zurich’s experience shows that a robust plan for a coordinated, expanded system, can not only win at the ballot box, but lead to the transformative results that transit riders are so desperate for - and which sadly haven’t been the result of past Bay Area regional measures.

The Bay Area has talked about creating a network manager - our version of ZVV - for a long time. It’s time to finally do it - so that we can maximize our chances of success at the ballot, and finally begin delivering, with new funding, the coordinated system that riders have for so long demanded.

—

For more information about what a Bay Area network manager could look like, see Seamless Bay Area’s report Governing Transit Seamlessly: Options for a Bay Area Transportation Network Manager or SPUR’s A Regional Transit Coordinator for the Bay Area.

Seamless Bay Area, SPUR and other participants of the study visit held Zoom Webinar on August 10 from 1-2pm PST, Lessons from Switzerland for Bay Area and US Public Transit. Here is the recording: