Technology, Emerging Mobility, and Applying Swiss Practices in California: Summary of Day 3 of the SwissCal Conference

Day three of the SwissCal Conference took place on February 22, 2022. This post contains a full summary - however, some of the main takeaways included:

Key lessons:

A successful recent innovation in transit customer experience in Switzerland is an app that automatically calculates the best fare when users swipe right or left as they begin or end their journey. Now expanding across Europe, the app, developed by FAIRTIQ, relies on several important conditions in Switzerland’s transport ecosystem: Existing rules & regulations (including common definitions of users, the common NOVA database) and pooled marketing and investment in the technology among operators.

Switzerland employs a national strategy regarding emerging mobility, including a national car share operator. It is integrated with the national public transportation network, in terms of both the planning of the networks - pods of shared vehicles and bikes placed at key hubs - and integrated on fare payment products and media.

The state of California’s approach to transit and rail planning is adopting Swiss practices. The state supports the establishment of distinct roles and responsibilities for different levels of government in California (strategic/network planning, implementation/project development, and service delivery); service–led network design principles (structured timetables); and a phased implementation approach for major infrastructure projects (long-term development).

Day three of the conference focused on the use of emerging technology in the Swiss transport system, and understanding how the various Swiss practices discussed over the conference sessions are being adopted by the state of California. Presentations from Jonas Lutz, Head of Product and Marketing at FAIRTIQ, Arnd Bätzner, Member of the Board of Directors at Mobility Carsharing, and Kyle Gradinger, Division Chief in the Division of Rail and Mass Transit (DRMT) at Caltrans wrapped up the final day of presentations.

One Swipe for Your Entire Transit Journey

Lutz introduced FAIRTIQ, a Swiss mobile app launched five years ago created with the aim to make a rider’s journey easier. Through a single swipe, a transit rider can travel from one destination to another, accessing any of the 250 Swiss transit operators, without knowing which service provider they will use, how much it will cost, or having to pre-load funds. Agencies receive the appropriate revenue, while also benefiting from origin-destination data as a by-product of this system.

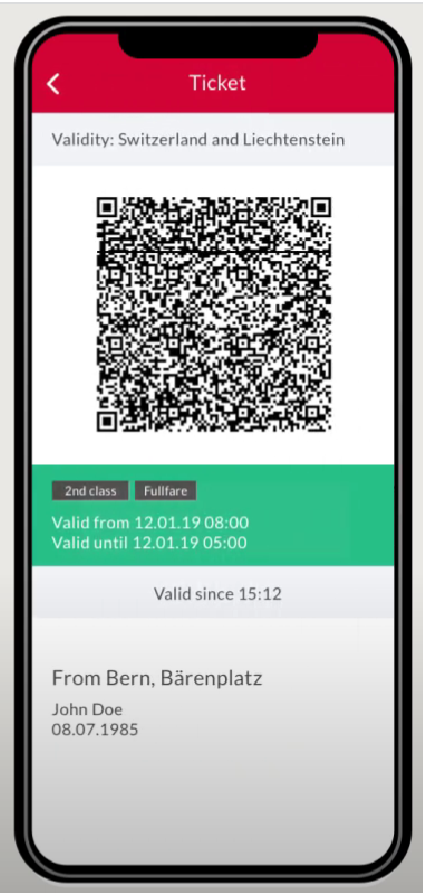

To use the platform, a rider swipes right to begin their journey. The rider can then use it on any system. Once the rider has completed their journey, they swipe left to end their journey. FAIRTIQ automatically buys the correct ticket based on the smartphone’s location. How the FAIRTIQ app works is demonstrated in this video and is also captured in the images below.

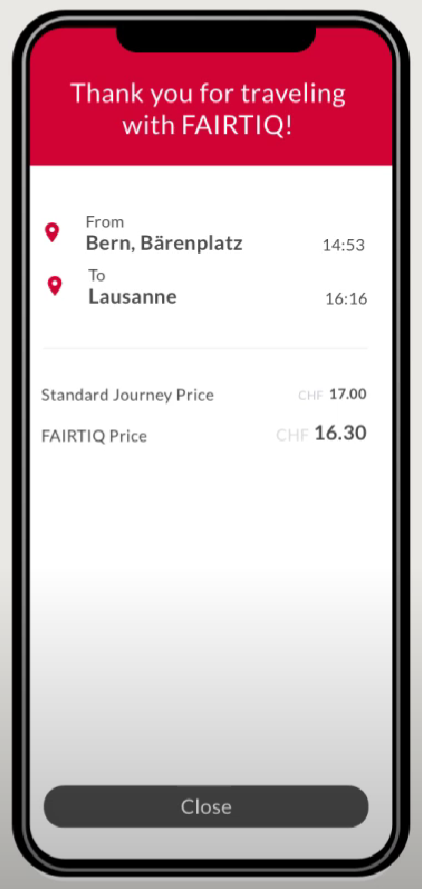

When the rider checks in (swipes START from left to right), they begin their journey (image 1). The correct ticket is then generated for the user based on the smartphone’s location (image 2). The rider can show the ticket to ride on any system (image 3). Once finished traveling, the rider swipes left to end their journey (image 4) and then an optimized ticket price is generated according to tariff rules (image 5).

Within five years, FAIRTIQ has grown from use on just three initial operators to all 250 operators in the system - without having to go through 250 Requests for Proposals (RFPs).

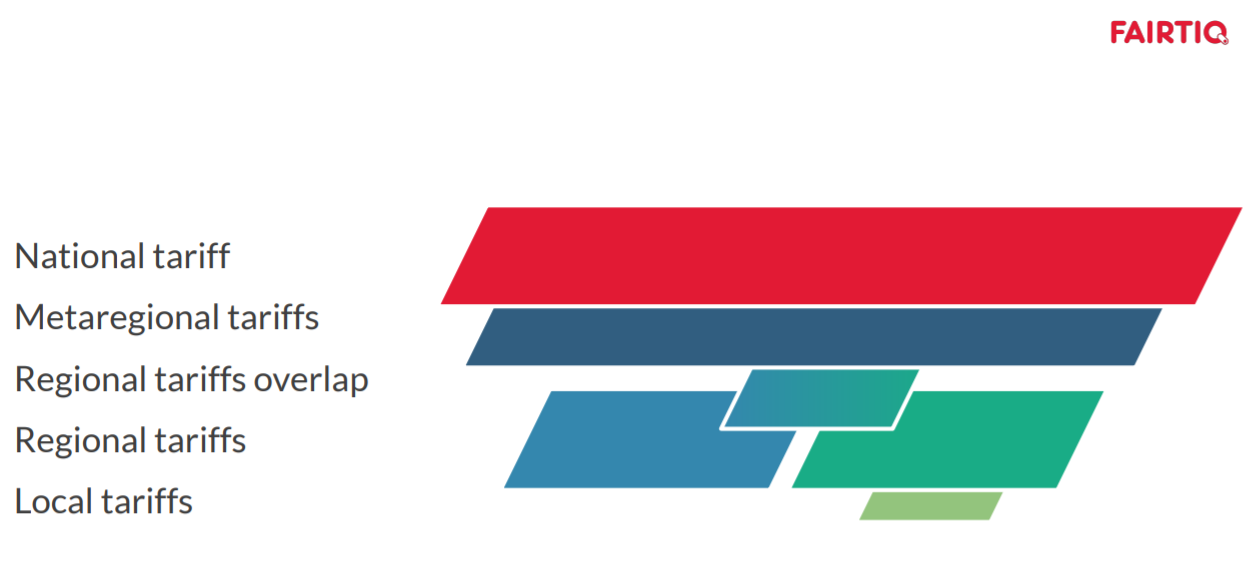

In Switzerland, there are five layers of tariffs for public transportation: local tariffs (short-distance prices), regional tariffs, regional tariff overlaps, metaregional tariffs, and the national tariff (direct service).

After a rider completes their journey, the app checks from all those layers of tariffs to determine the best fare, taking away that burden from the user.

In Switzerland, transactions are not handled by FAIRTIQ, but by regional transport authorities and providers. FAIRTIQ licensed out their technology to SBB and made them the operator in charge of the mobile platform.

FAIRTIQ’s success in Switzerland is built off several conditions related to the Swiss transport ecosystem’s overall structure:

Close collaboration and mutual trust among operators

Leveraging existing rules and regulations and creating new rules only where needed: There are already integrated fares at the regional level and established statewide, distance-based fares in which all operators participate. Additionally, there are designated agencies who distribute cash collected.

Cross-selling of tickets and having a central broker (the NOVA system)

Common definitions: A child is a child everywhere (someone under the age of 6). Children travel for free.

Common standards: Barcode standard for tickets (started as an SMS standard then a QR code that can be retrieved through the NOVA platform)

Understanding barriers and pooling resources: FAIRTIQ had worked in distribution ticketing before at SBB, so they knew developing and creating an app would be challenging for operators and challenging to maintain. Thus, they pooled financial resources. Every new partner that joined would pay its share of a reasonably-priced technology that it would not be able to finance itself. As a result, there was no need to reinvent the wheel; one app is available everywhere, is easy to use, and remains the same across operators.

Open-source data: FAIRTIQ does not have run after all the data as SBB provides General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) data for each transit operator.

Lutz concluded that the establishment of similar conditions and standards in California would support the expansion of customer-focused fare payment tools like FAIRTIQ.

Emerging Mobility as an Extension of the Public Transportation System

Arnd Batzner then discussed how emerging mobility integrates with public transportation in Switzerland.

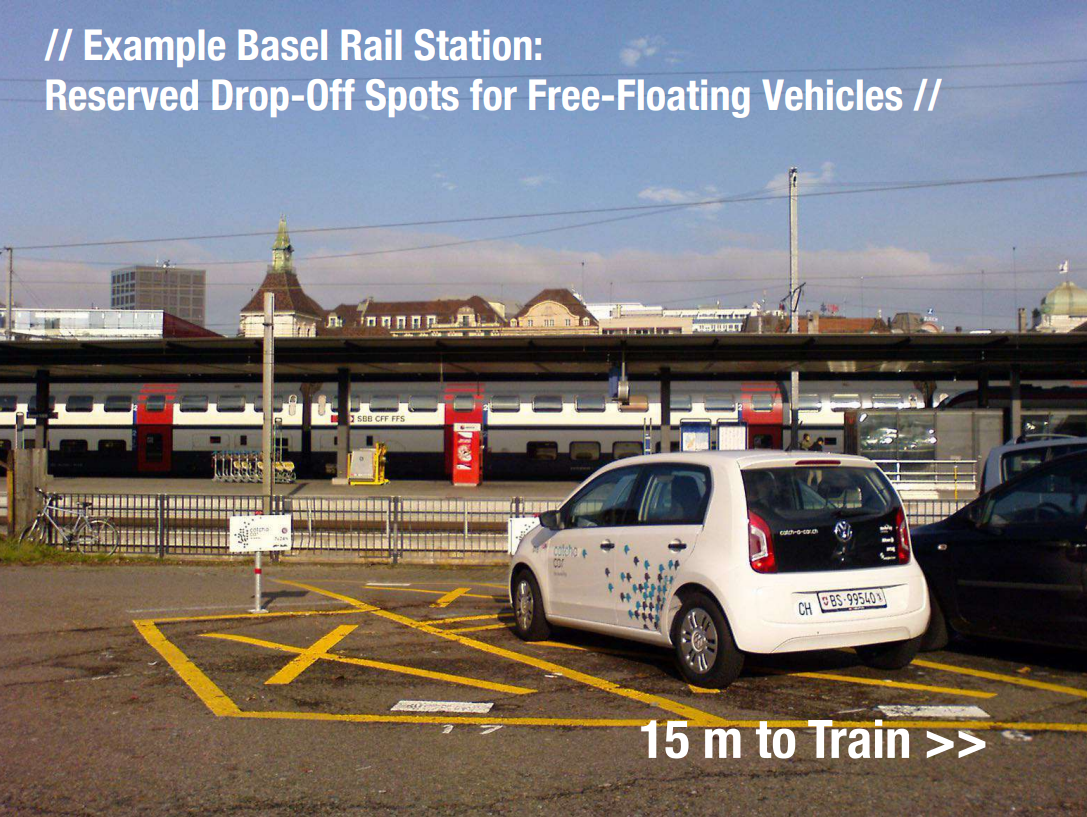

He described how Switzerland has a national strategy with regard to emerging mobility, especially carshare, which is integrated with the national public transportation network. Mobility Carsharing, which covers the majority of organized carshare in the country, has 1,300 carshare pods nationwide, leveraging public transportation hubs for its vehicle locations.

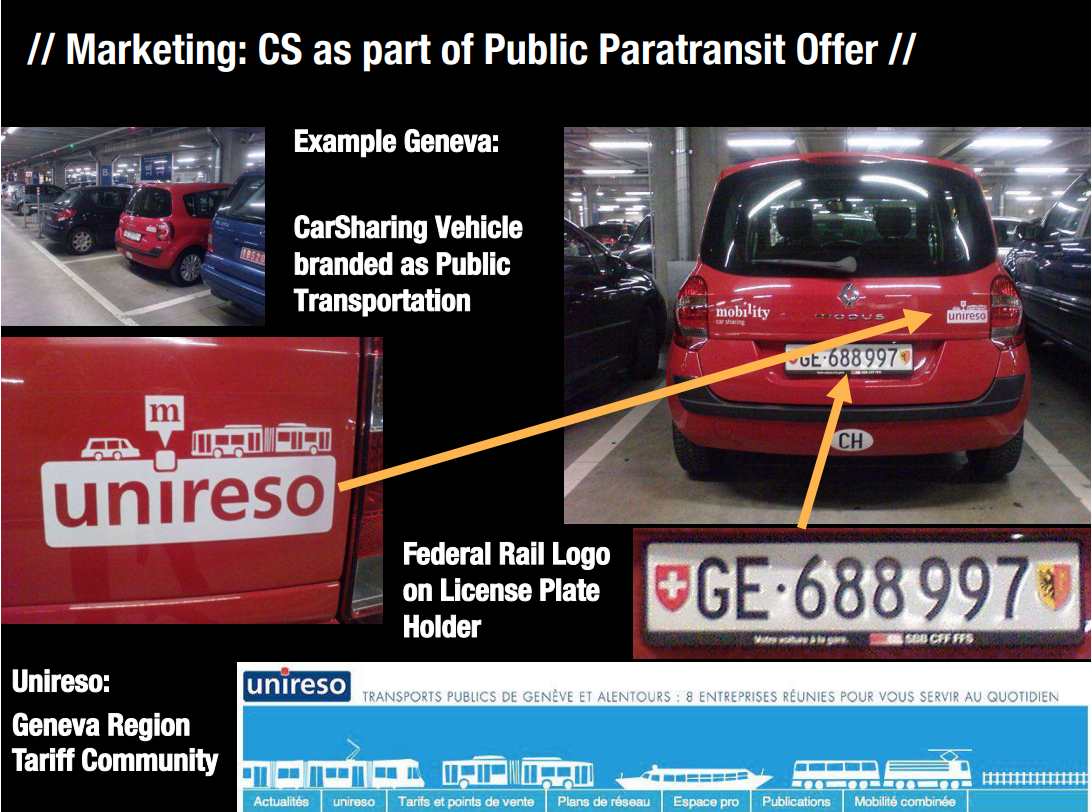

Carshare vehicles are branded with public transportation provider logos, signaling that they are part of the national public transportation network. This shows they are not a private vehicle, but a public one.

The carshare vehicles offered include both round trip and free-floating (one-way) vehicles, serving the different needs that users might have. They are available at convenient locations like different airports and rail stations. In addition to carshare vehicles, Mobility has also rolled out scooters that travelers can use. All of these modes can be unlocked using a SwissPass, the national ticketing system.

Mobility works with regional rail providers to prioritize access close to train platforms.

The 2022 California State Rail Plan: Swiss Inspirations, California Applications

Kyle Gradinger of Caltrans then discussed how Swiss practices are already being adopted by the state of California, highlighting three specific areas of Swiss inspiration:

Setting effective roles and responsibilities;

Service-led network design principles (a structured timetable);

Phased implementation (long-term development).

Setting effective roles and responsibilities

The matrix to the right outlines what Caltrans envisions as the function of different public transportation players in California, similar in approach to the role of different actors in the Swiss public transportation system.

Gradinger emphasized that having effective transportation network integration demands that California has effective planning and governance integration. Currently, there is confusion about roles and responsibilities which leads to siloed efforts and duplicate work, as well as stranded investments and incompatible solutions. As a result, users face the consequences of this uncoordinated governance every day. Thus, having a clear strategic planning framework and network design principles can be used to guide downstream implementation planning and project development. This approach ensures service delivery is consistent and serves the public good. In this vision, each transportation entity should be able to develop the analysis that is appropriate to the level of detail and technical precision for the task. This will require significant coordination across different levels of government.

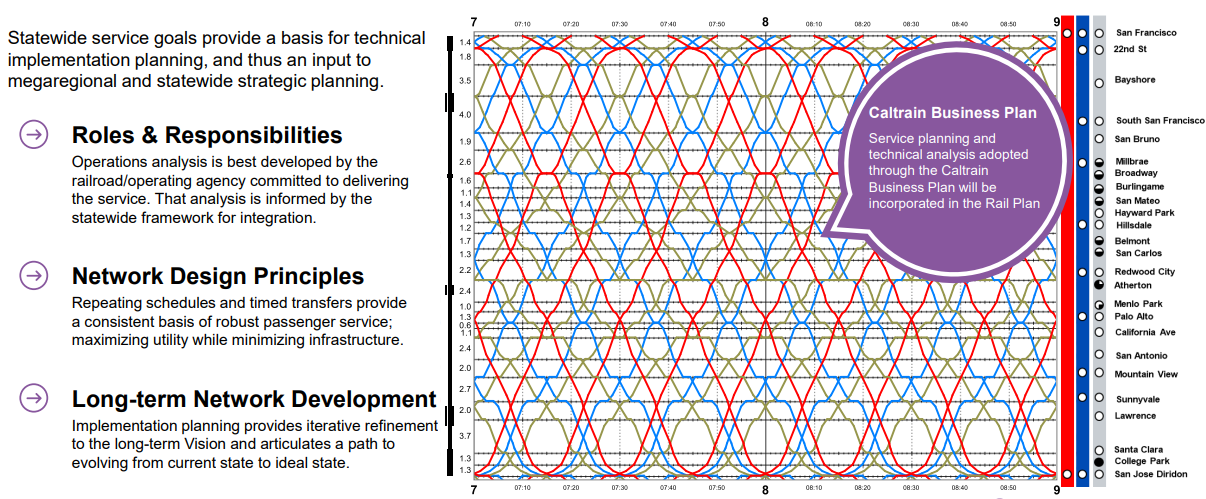

Service-led network design principles (a structured timetable)

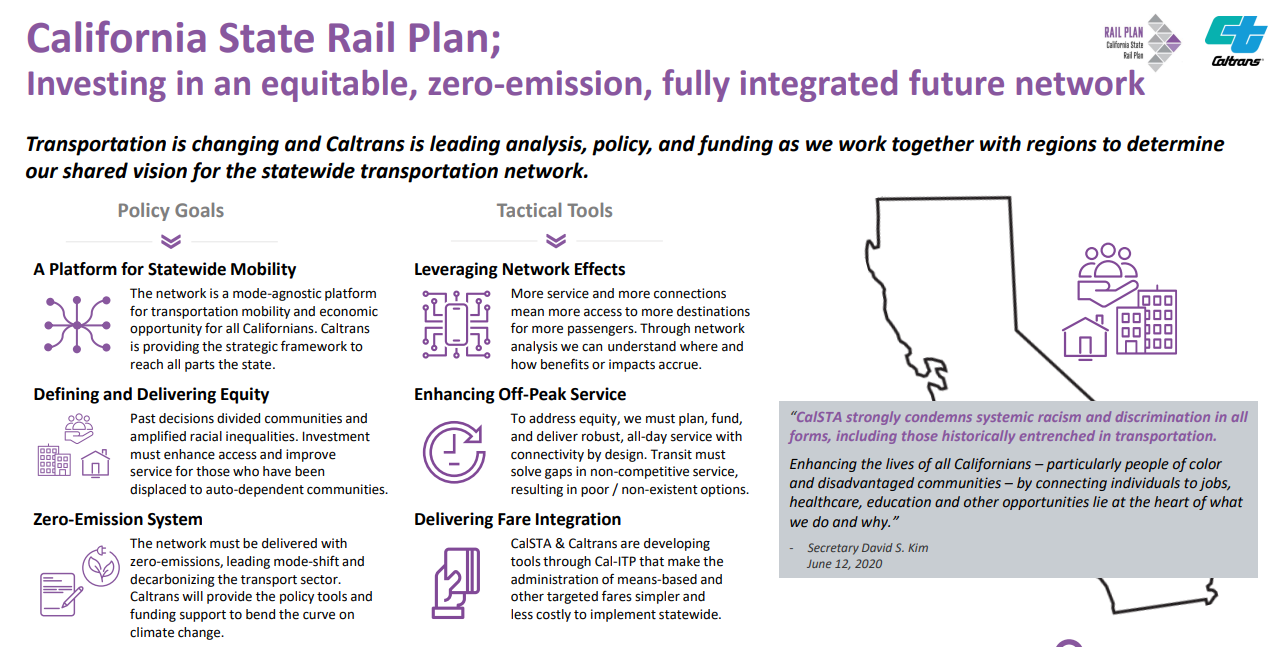

Policy Goals and Tactical Tools within the California State Rail Plan

Caltrans is planning for designing a future with an integrated statewide network with similar technical approaches to the Swiss. Specifically, it hopes to design a statewide service planning framework around connected hubs or transfer nodes and delivered through repeated pulse schedules (structured timetables) where trains will meet at stations at regular intervals, reducing travel times and ensuring connectivity throughout the network. Ultimately, this will also minimize capital costs and operations costs.

The agency is developing a 2022 California State Rail Plan that will have a 2050 long-term vision. The Rail Plan establishes California’s strategic vision and the framework for partners to coordinate.

Caltrans seeks to lead analysis, policy, and funding at the statewide level, while working with regions to determine the shared vision for the statewide transportation network. They are working towards planning and funding a mode-agnostic platform for statewide mobility for delivering equity (moving from peak-hour service to robust all-day, competitive service with designed connections between services) and responding to the climate emergency. They are also working to deliver statewide fare integration and design-targeted fare discounts by working with the California State Transportation Agency to develop the California Integrated Travel Plan (CAL-ITP).

Phased implementation (long-term development)

The case study of the Monterey Bay Area Rail Network Integration Study exemplifies both the application of the Swiss service-led network design principles and the Swiss approach to phased implementation. Caltrans worked with the Transportation Agency for Monterey County (TAMC) to develop a service-led plan focused around hubs with pulse schedules, with connections to future high-speed rail in Gilroy. At the areas where the network comes together with branch lines to Santa Cruz and Monterey at Pajaro and Castroville, they focused on the opportunity for trains to meet there and design the infrastructure around that need. In terms of phased implementation strategies, the technical outputs were seamlessly incorporated back into the statewide models in the planning toolkit, and future iterations of regional implementation planning in the Rail Plan will be derived from that tool. This study provided a technical basis for future project development and funding coordination with the state’s class 1 freight partners and state funding for initial service in the short term.

Case study: LOSSAN Optimization Study

These are matrices of every Pacific Surfliner, COASTER, and Metrolink commuter rail station in Southern California. The left is how many times a day one can reasonably connect from one station to another; there is a significant amount of red, meaning that a passenger can connect from one station in the mega-region to another at most one to few times a day. After a service planning process (shown on the right), the number of places that one can connect to at least hourly, or sixteen times from 5am-11 pm, increased exponentially. After this study, Caltrans and agency partners realized how planning for connections by design vastly improved the origin and destination pairs that could be served in a given day.

Gradinger cited the LOSSAN Optimization Study as an application of Swiss principles. LOSSAN is the managing agency for the Pacific Surfliner inner-city passenger rail service between San Diego and San Luis Obispo. The study is an effort to analyze future growth and improved mega regional connectivity in Southern California. Through the study, they developed technical passenger service plans as a tool for improving regional connectivity and providing an input to future freight coordination.

In terms of roles and responsibilities, Caltrans determined that it was best led through local stakeholders. In this case, LOSSAN worked very closely with Metrolink, the North Country Transit District of San Diego Country, as well as other partners like LA Metro and SCAG.

In terms of service-led network design, the plan leveraged network effects to expand the market to serve more trips, make better use of operations funding, and reduce the overall capital investment needs by getting away from infrastructure-led planning. This provides a basis for passenger rail and transit growth in the region.

In terms of phased implementation strategies, the technical outputs from this effort are being incorporated back into statewide models and future iterations of regional implementation plans.

Finally, the Caltrain Business Plan was cited as a further example of the application of Swiss principles.

In terms of setting effective roles and responsibilities, Caltrain was able to leverage this strategic framework for a long-term vision of blended service between Caltrain and high-speed rail on the Peninsula corridor.

In terms of design principles, the statewide network design principles for regularized scheduled timed connections and pulse style service allows the corridor to serve local express and high-speed service while minimizing additional infrastructure investment.

In terms of phased implementation, the technical work developed for the plan provides direct input to statewide modeling of future iterations of the Rail Plan and other regional efforts like Link 21 (the new Transbay passenger rail crossing between Oakland and San Francisco).

Gradinger closed by mentioning that the success of the Swiss network provided not just aspiration, but inspiration, for California. It did not just inform the network that California wishes it had, but instead it informs how it will plan, design, and ultimately deliver it.