Timely new research on ‘world class’ transit systems offers striking lessons for Bay Area

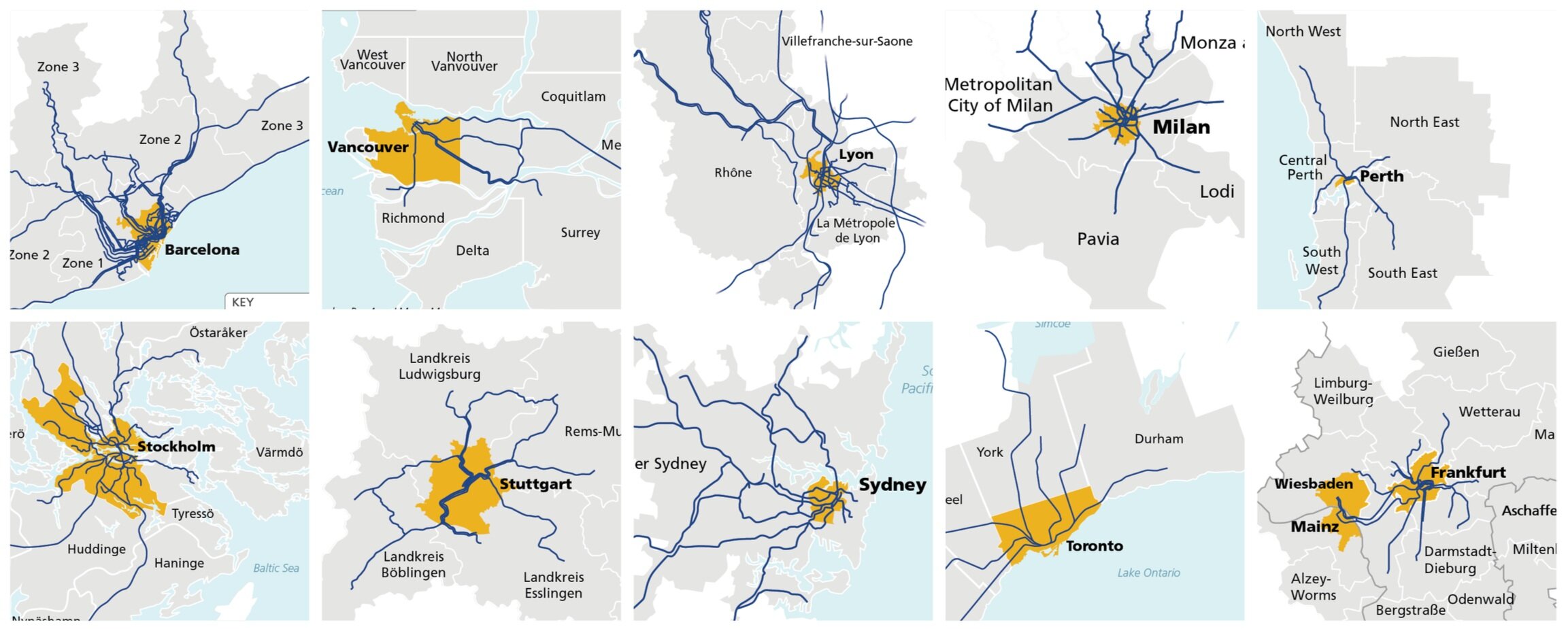

The ten case study regions profiled in the forthcoming research were selected to be comparable to US mid-size metropolitan regions in terms of income, automobile ownership, and land use patterns where possible, yet have achieved much higher-performing and widely used transit systems. In all but one of the case studies, per capita transit ridership is significantly higher than the Bay Area’s, ranging from 34 per cent (Vancouver) to over 400 per cent (Stockholm) higher. In all but one of the case studies, the total transit mode share - the share of all trips taken on transit - ranged from 12-37% of all trips, compared to Bay Area’s transit mode share of just 4% of all trips. Image Credit: Moses Maynez

Seamless Bay Area’s vision for public transit in the Bay Area is a “world-class, integrated, and equitable system”. But what does the term “world-class” mean? New research from the non-profit Transportation Choices for Sustainable Communities (TCSC) entitled “Characteristics of Effective Metropolitan Areawide Public Transit”, funded by the Mineta Transportation Institute, helps us define “world-class” transit, and what institutional structures, policies, and funding are associated with it. The ten metropolitan regions profiled, spanning seven countries, offer powerful and timely lessons for Bay Area transit leaders, elected officials, and riders as our region reimagines transit in a post-COVID-19 era, and decides whether to reform transit institutions to support moving toward a seamless and high-ridership system.

Seamless Bay Area had the opportunity to review a preliminary draft of the research paper. In this blog post, we summarize what we believe are the four most pertinent lessons from the research for the Bay Area right now:

High ridership transit systems exhibit similar qualities of regional integration, affordable fares, plentiful frequent service, and coordinated schedules.

All case study metropolitan areas had an effective “Regional Transportation Coordinator” - or “network manager” - entity that oversaw a similar set of transit system functions, regardless of how many transit operators were in a given region.

While several different institutional models existed across the case studies that achieved coordination, a common characteristic was clear relationships between jurisdictions, transit agencies, and the network manager entity.

Each region took a different path, but state/national legislation played an important role prompting and/or streamlining coordination.

Seamless Bay Area and SPUR cited the research’s findings in their joint presentation at the September 14th Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force meeting to help guide the group’s discussion about what should be part of the “Bay Area Transit Transformation Action Plan” being developed by the Task Force by mid-2021.

To discuss how these research findings can help the Bay Area turn a new page in its transit history, Seamless Bay Area and SPUR hosted a free webinar on September 10th with lead researcher Michelle DeRobertis, P.E., and Vancouver-based transit governance expert Tamim Raad entitled Transit Governance: Lessons for the Bay Area. Check out the recording above.

Integrated, affordable fares; coordinated schedules; frequent, abundant service

“Without exception, the ten case study metropolitan areas have moved toward a single region wide integrated fare policy, most having fully embraced it,” the authors state, also citing research in the US and abroad that implementing single-ticket journey-based fare policies are associated with increased transit use. Many of the case study regions had widely available affordable monthly passes that provided unlimited access to all forms of transit within the region - something that simply doesn’t exist in the Bay Area.

For example, a monthly pass providing for unlimited transit within the greater Milan (Italy) metropolitan area’s 9 different transit systems, is just $96; the equivalent unlimited pass in greater Lyon (France) is $86; in greater Stockholm (Sweden) just $96; in greater Stuttgart (Germany), $245. Someone wishing to have unlimited travel on the Bay Area’s six largest transit systems would pay over $750 for five different monthly passes - and even then, they wouldn’t get access to BART, which has no monthly pass at all.

Nearly all case study regions exhibited regionally coordinated service, schedules, and customer experience, creating seamless, quick transfers and promoting multi-modal transit travel A focused analysis of four of the case studies - Stockholm, Vancouver, Lyon, and Barcelona - found that coordination can lead to increased ridership on its own, without high levels of additional spending and subsidies. Nevertheless, the authors find that regional coordination is found to have the greatest impact on ridership when combined with higher levels of investment and service.

Existence of a Regional Transportation Coordinator - or “Network Manager” entity

One of the most powerful observations made by the researchers is that all ten of the regions studied have a “Regional Transit Coordinator” entity that oversees a strikingly similar set of regional transit system functions. These functions include long range planning and service design, fare policy, schedule coordination, procurement, and monitoring of service quality.

[A side note about terminology - Seamless Bay Area opts to use the term “Network Manager” when referring to this type of entity, as we believe the term “coordination” in the Bay Area has a generally weaker meaning than when it is used in other contexts. By using the term “Network Manager” we also wish to avoid the suggestion that MTC, which often describes itself as the Bay Area region’s transit coordinator, is equivalent to the more active Regional Transit Coordinator entities profiled in the research.]

The following table, extracted from the research, summarizes the ten metropolitan areas and all the various functions completed by the Regional Transit Coordinator / Network Manager entity in each case. The final row is our assessment of which of these functions are managed regionally in the Bay Area.

Summary table, by Seamless Bay Area, based on data presented in forthcoming paper by DeRobertis, et. al. “Characteristics of Effective Metropolitan Areawide Public Transit”, indicating that network managers in the ten case studies oversee a similar set of functions.

The comparison between the ten case studies is striking - the network managers in every single one of these effective regions oversee long range planning, system network design and schedule coordination; in all but one the examples, the network manager enforces service standards; most also manage integrated fares, procurement of operator contracts, marketing, and branding. By our assessment, none of these functions are fully coordinated within the Bay Area, illustrating the Bay Area does not have an effective network manager.

Multiple Models of effective Network Managers

The research not only points out the existence of effective network managers in each of these regions, but helps explain how they’re structured and governed. The authors point to three different models for network managers, all of which can be effective:

Coordinator Only: The network manager entity is the coordinating body of many individual transit systems owned and operated by different governmental political jurisdictions at different levels of government: cities, provinces, regions, and/or the state.

Coordinator and Regional System Owner: The network manager coordinates the system and also owns and manages the regional (but not local) transit systems.

Sole System Owner (Complete Consolidation): All public transportation in the metropolitan area is run by one agency, and this single agency is by default the network manager.

Summary diagram, by Seamless Bay Area, of the three conceptual models of Regional Transportation Coordinators / Network managers explored by the research of DeRobertis, et. al. “Characteristics of Effective Metropolitan Areawide Public Transit”.

An important lesson this research demonstrates is that across all of the ten case studies and three models, there is a clear relationship between the state and local jurisdictions, the network manager entity, and transit agencies that provide the service. The authors state:

“[In the case studies], it is the cities, counties, and states who have the direct responsibility for providing public transit within their political boundaries, ensuring that it is planned, funded, and operated... The fact that these governmental political jurisdictions— which have legislative as well as taxation authority—are also the transit agencies seems to provide a greater level of ‘ownership’ in the performance of the transit network on the part of local and state governments.”

We think this is such an important point, especially relevant to the Bay Area, that we’ll be unpacking it further in a future blog post.

State legislation prompted and supported coordination

Finally, the research is clear that there is no single path toward a network manager; in some cases (Frankfurt, Toronto, Vancouver, and Sydney), state or federal legislation prompted reorganization; others, such as Lyon, France evolved toward more bottom-up coordination, with legislation serving to formalize and streamline coordination. In most cases, reorganization was not a one-time event, and multiple pieces of state or federal legislation shaped the network manager and its precise set of responsibilities and funding over time, occurring iteratively with regional growth.

This seems like a particularly important lesson for the Bay Area, where despite significant growth since the 1960s when many of our existing regional institutions were set up, the region has shown an aversion to significant alterations to transit agency boundaries, mandates, or governance structures. A prime example is BART, which has grown far beyond the three-county system it was created as, but hasn’t adapted its governance structure to reflect this.

More than anything these case studies show us that regions that have better transit systems than we have proactively reshaped their transit institutions to deliver service that is efficient, connected, and customer-focused.

-

It may seem difficult to consider this research as relevant to the current crisis we face, where the devastating effects of COVID have put our entire transit system in peril of collapse. Without further funding for transit from regional, state and federal sources, deep, permanent cuts to transit service are all but guaranteed, and shutdowns of some services are likely. Let us be clear - better integration and coordination, enabled by reformed transit governance and an accountable network manager, will not solve our transit funding crisis.

However, the Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force has, appropriately, been tasked not only with identifying how to align transit agencies toward a near-term recovery, such as by aligning safety procedures - but also with developing a Transit Transformation Action Plan to create a higher ridership, more connected network. These case studies show that a network manager and seamless integration are essential components of the transformation of Bay Area transit into a high ridership system. The research acknowledges that without more funding and investment, the impacts of that coordination will be more limited - but nevertheless worthwhile.

Battling COVID has often been compared to fighting a war. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the United Nations, which was founded on April 25, 1945 at the tail end of World War II - in San Francisco. The UN was created to promote global cooperation and avoid future major wars - and, for all its faults, it has largely succeeded, proving to be one of the most important and resilient global institutions promoting peace and human development. But planning for the institution that became the United Nations didn’t begin in 1945, when the war was nearly over - it started at the depths of the war, in 1942, among visionary leaders. The foundational discussions among the Allies that led to the UN as we know it today started prior to anyone knowing exactly when or how the war would end.

While fixing Bay Area transit is clearly a challenge of a different magnitude of averting world war, the example underscores the importance of thinking about the near-term and the long-term in parallel. The work of identifying the right approach to developing a network manager for the Bay Area should not be put off for some future year. It must begin now, complementary and parallel to transit agency-led recovery and coordination efforts. We don’t know how or when COVID will end - but it will end, and we need to have a plan in place for our long-term future.